Welcome to Is(sue) 14, Kinfolk! Thank you for loyally contributing, reading, and sharing! It is you who make this ezine and you who keep it breathing. The fifthteenth regular is(sue) will go live on June 15, 2024. See Sub(missions) in the menu (for more information).

|

|

|

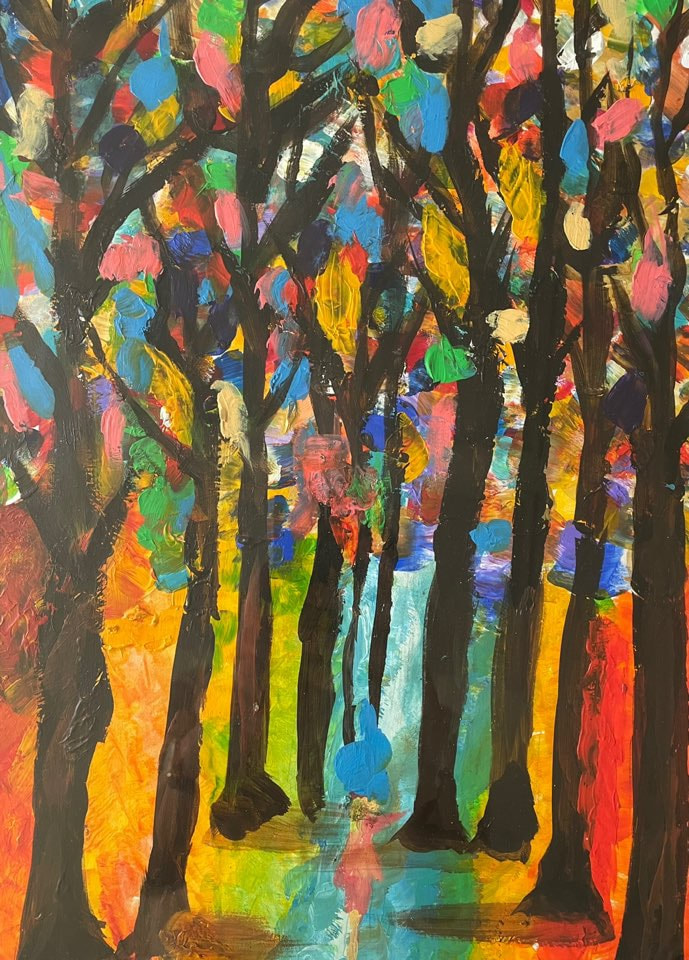

"your heart, flying"

R.Bremner, New Jersey |

|

your heart, flying through the high sky, tries to regulate its anxiety before the urgency of your

child earth ticks its time bomb to rest from the stress of your systemic manipulations. "Solecism of Spring"

R.Bremner, New Jersey For a taste of organic

hubris, raining down from the sun on this fifteenth of May we need only smile in our degradation, humiliation, outpacing in growth our garden tomatoes today planted; For a taste of earthy salad, a lesson in orgasmic logic -- laugh for the sun, it shines while you work, secluded, in its teaching sweat; laugh for this man, this solecism, this devilclown (who dares rue, simplistic), who runs with words and leaps, who defines disco by his gorgeous: laugh for yourself, in the noiret of simplistic, carve dragons out of soap, and be, in the light of the funeral pyre, yes, BE. turn degradation into song of celebration we have merely to be solecism, orgasmic of the spatial plane, beyond humiliation into the realm of laughter’s reign; who laughs will not be drowned, but shall drink hubris rolling on the tongue as fine as Verdicchio, till warmly swallowed organic of the festive solecism, the unpicked tomato. "3 Days in a Coma"

Sakariyahu Abdulwasi'h Olaitan, Nigeria v.

His mother earned an interim farewell as he went to bed upon his own accord. With empty vows on his body and pale farewell whispers in his eyes, he titled his doctor with the sound of winds intruding on a centuries-old wireline conversation. Cultivated. The leaf of nods,which portrayed as fireflies whirling on an orchard's peak became orphans as a result.To his pals, he'd been orphaned. He'd been orphaned. iv. Golden cheeks led into a sea of hurdles. As we flipped another page of the album & mounted his photograph within, our hopes of a smooth homecoming were buried at the garden of our frustrations. Dead. Dead. Dead echoed Perhaps sometimes you failed to lust for someone to live on yet another moon on earth when you gaze upon them languishing in bed while sickened. Better than climbing uphill.The dua. Amin! Amin!! Amin!!!.. iii. Second day in coma His age is immobile and has his eyes tightly shut. Uninspired. Motionless. While whispers of glee fade, the hands of time remain to twist and turn. A heart's prayer dances in the darkness waiting for him to be no cost; an orchestra waits, we see in the silence. Rewrite the boy's fate by rekindling him.Trembling heart/fragile thread/a fateful bind. Doctor's words: - 12 percent// "70 percent, blood must be located," "searching for hope/a lifeline," "sun dips low/casting shadows on despair." We fight brutal fate in spite of frantic whispers. Before light blows away, a donor must make an appearance. ii. agreed to offer its whole bloodline, their blood, just to gain insight that "there's no matching" Okay, When the benevolence of twelve folks came up for grabs A frayed bond, There were no marvels to be found in kin's veins. Lost within the framework that DNA designed, but the essence of love defies biological genre. i. Third day in coma A true brotherhood, his uncle's blood upon completion worked for him. He was birthed again, the dead sprung into healthy flower, hearts were roused, all hope was restored—a celestial stroke. hidden miracles, Oh,what an image. Al-Hamdulillah. Al-Hamdulillah. "Late Laments of a Weapon"

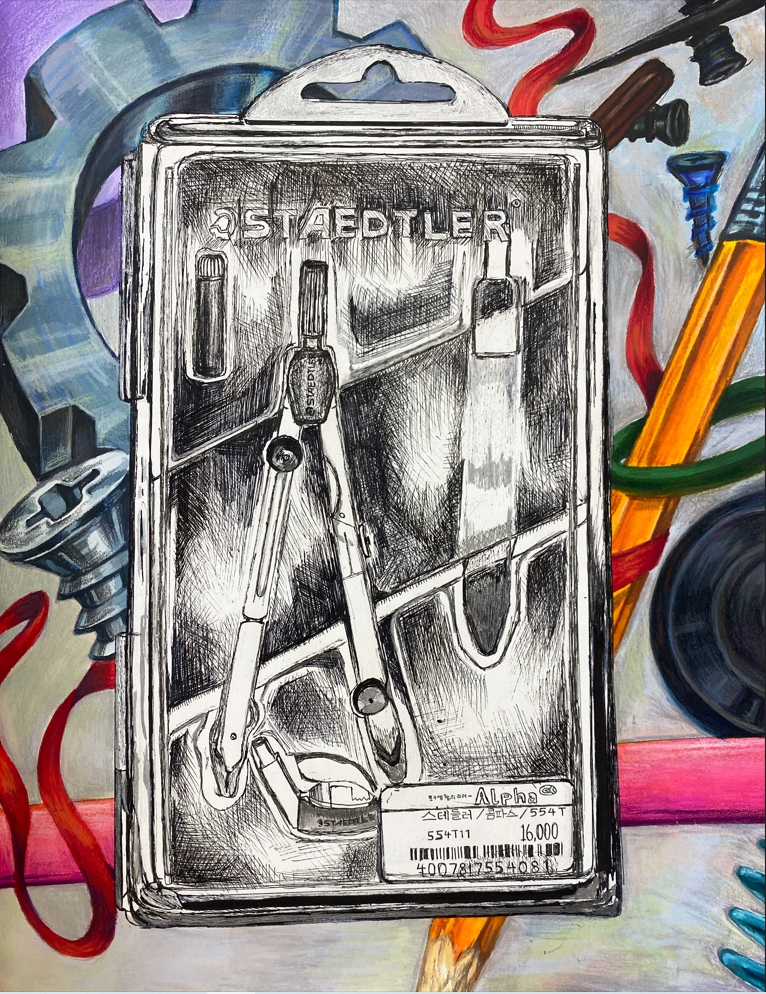

Yoon Park, South Korea I.

They made my body out of screws and nails but I made my name Out of the shards broken from the corpse of a dying star. One man against the new world. One man against the Hands that made us And one man with the hands that guide the hands, but only After I left the remains of the name that my Maker gave me In whatever corner drug store that secretly sold spirits and cigars To the likes of me, because I left a pinky finger-length of my conscience Picked up a handful of humanity on the way out, and an ounce Of my dignity pumped like blood upon a surgical gurney. What a pity. Here’s a little secret I should let you in on, (Perhaps the greatest error Is believing that my heart is made out of something real and organic Instead of the humanity that slipped between my fingers the moment I picked it up like sand. I’m so sick of explosions under my eyelids When I close them so I don’t close them at all. My good dreams are Wires and metal alloy and the first taste of a bomb in my mouth.) And this is the conundrum that’s keeping the stars apart. Finally, like the turning of an age, They speak to me: This cage is too small to hold your galaxy; open wide. I press my face into the dirt and close my eyes. II. I could call myself / a super-luminous spheroid of plasma held together / by self-gravity / buttered by what I hope is / a greater purpose— they called me / miracle but instead I call myself / antimatter & the night / is dark / but the star is bright. / It’s too bright to focus on / but when I put a hand over half / of it I can see / its bubbling edge / where the molten hydrogen boils / constantly & / I am alone / again. My back hurts something fierce / when it rains fire. I tell myself / I told you so. III. He feels like an intruder in this peace. Like he taints the ground he treads on with greasing oil, his head filled With impossible knowledge, a child in him taken apart and reassembled For destruction. That night he leaves the house before sunrise, chased By a formless dream of falling through space. In the greenhouse His flowers are getting ready to bloom. The house is waiting to wake up; He thinks he has to solve— something— before waking up with it Because this body is malleable, it just grew mimicking The home that others have instead of the house that fits Him like borrowed clothes. At the center of the still dark water he lays on his back and looks at the sky. I don’t belong here, he mouths desperately, angrily, almost like a dare And goes to watch the moons rising in the lake. IV. Good morning, I simply say, because I want it to be. V. perhaps I would not prefer to function like clockwork but rather as a mere headless man pretending to be human because of that sense of comfort knowing there is no predictability in where I am going and that might be a good thing, maybe for (me) a prototype amalgamation of biological components & artificial tissues & a convoluted skeletal structure once supple now mottled; our limbs where we cling to are as fragile as the heart I sculpt its own cracks— the seafoam fragments of what I love, my manufactured flesh & my curve that rests upon the table haven’t been left untouched or unspoiled I said, fashioned by a rounded tongue & eidetic muscle memory, it is the anatomy of us; perhaps, if you turned me inside out I wouldn’t look anything different than I do in my own skin. "Each Set Reinforces Scalding Heads"

Joshua Martin, Pennsylvania chastise both axes - - - ‘tis common

hacked factoid - - - [ distraught monsters forsaken accidental thunder ]. horse’s foot, drowning bone powder w/ ease. one bag contains visionary miles , coastal flooding felicity , walking Ring Casket Bosom. Buddy, dwelling percentage , servants , , priggish shine : a Gnat , a Flea , , sobbing boats. shall break the traveler in a manner befitting chorus rhetoric. hum. gone: page by page , an estate worth choicest miserable lacky, , ellipsis . . . [gone mirth remedy] . . . thickets & whatsoever, qualities rouse thoughtless cyclones. hirsute shame , boundless ease [ methodology informs sculpted groundings] , opinionated pretext, omnipotent proposal. gouty frowns , , , , , impatient squint, absent tools, caring statues w/ a kind of synopsis unrelated to Beauty. portent. a dragging brooch against laudable scams , squirming crawfish unleashing swaying verses. Laudable : Parades gone to invent cannibals. facades melt away, storing finite symptoms , aging & conclusive exploratory popsicle mattresses, outrage spoke to Enlarge [flight] / [feeding] / / [causes] : lunar facial escapades, encase an hourly wage , sluggish amendments. looping & idle proclivities, a matter of diet. understated barefoot cloth, use, moderate skill, ‘twas a recent temperament to Blast comical honeycomb speedometer. "Coming Down"

Charles A. Swanson, Virginia rain falling dims horizons grays blanket distance drawn close

smothers sounds muffle flannel lowers like breath my thoughts close in coverings like metal in a bowl inner light flickering breath hushed waiting tense guttering winds finger fine hairs quiver for thunder for lightning this body this day these fears this world this shuddering "Pocahontas at London"

Olchar E. Lindsann, Virginia castaway She ,sillkstay cinch ,forsaken

smog-smear cloud-caved London lost grime autumn in, Rebeccy falling ,werowance-shorn Salvage Princess crowd-wave-swallowed ,brick ,forlorn ;She watches tongues wag white tail bound cross seas-hurl ,bible sound of match-lock ,mispronounces beaver skin – that yawn’d-out yowelroll’d English code: brick lined entrail :tis a Street stuck with fecal refuse-stink of English; gaping council stare of clown-paint powder withering simper’d-grin :tis Court ,calls English; cliff -cut square-cell hive night hung in closure :tis Fine House Indeed ,tongued English; rhythm square-cut, mantle -burthened ,salt licked chatter venison :tis English Fête; sweat-caverns chill flockd seating sachem preaching stone ,tis English Church; silk mob horn-blare’s blinding-glint of polished clay face drum procession dance: tis Masque for English; free-self-traiding, hunger-chain ’baccky-hoards ,rote-slap training ,rags tis English industrie; – all’sticky with ;sick :in brick-jug plugged as grainery-seed darktamped’s She ,bedpost fester spirit Bedchamber :trap ;Lo!: heed ye, reed-hoarse ,heady piping window peer: sees She below at dance most ,ring of ,nearly salvage mirth out there in hawk-clutch dear like, dances fawned and ,copper flicked at: ,her captive Baited cousin Bear ;strap-bound sways he mange ,bare-grinned dismall laughs via Muzzle , ribs ,castaway blackfur pang confederation ,She: “we few forlorn old world strays sea battered muck engulfed – dance cousin Bear our nation’s dying-dances ,for English Industrie ,our Blessed Husband ,binds ,coins ,advances...”

|

"John Brown and Sons"

JWM Morgan, California

JWM Morgan, California

Kansas Territory, Late Summer 1856

As I rode into the yard beside my troubled son Fred, Florilla Adair, my stern and admirable missionary half-sister, stepped out the cabin door into the morning sunlight holding her axe by the upper shaft, the edges of the blade shiny from fresh sharpening. The Adairs’ blond boy Charley, now twelve, and his little sister Emma grinned at Fred and me. Florilla and Emma each wore a dark blue dress: one full-sized, one tiny. The sight of the bulge at the front of Florilla’s dress ripped my heart. I had passed a rough year here in Kansas since I had last seen my youngest, Ellen, then a baby just approaching her first birthday. Now she was almost two.

In the mess of scrap wood in the yard, I saw the upturned leg of a table and two chair seats. A few weeks before, proslavery terrorists had dragged this furniture out into the yard and smashed it into pieces.

Florilla greeted Fred and me solemnly. “We are glad to see you. I am sorry I can’t invite you in.”

I met Florilla’s extraordinarily steady gaze and knew she and her husband, Sam, had fugitives concealed in the house. We needed to speak no more words about this. Florilla and Sam helped people escape north to freedom. I respected them for their commitment to human decency and for their daring.

A fowling piece fired in the distance. “Sam and Jason, out hunting,” Florilla said.

“Jason! I thought the army still had him in irons.” My sons Jason and John Junior had been arrested for antislavery activity two months before.

Florilla smiled in her subdued way. “Free man now,” she said.

“Thank God.”

She nodded. “For all he’s been through, he seems okay. Delighted to be back with his wife and child.”

“How wonderful! And John Junior?”

“Still in the hands of the federals.”

Officers of the United States Army, in their exasperated state of misplaced rage over our military actions at Pottawatomie, had arrested and tortured John Junior and Jason, who were, in this matter, completely innocent. By our government’s warped logic of crime and innocence at that time, “John Brown” should have been imprisoned and tortured, not my sons. By means of some strange intermixing of rumor and creative newspaper writing, I had become the most public enemy of the beloved institution of slavery. This was silly. I knew what I believed, a rare enough human trait, but I was only one person and a deeply flawed and modest one, at best. You might have thought the foundations of civilization were threatened, the way the proslavery editorialists wailed about our little activities on the borderline between righteousness and evil. It was amusing for me in a strained way, almost funny. Panic in the hearts and minds of the morally corrupt had a certain entertainment value, despite the vast panorama of torment on which this drama played. Above all, they feared losing their “wealth.” So sad.

Southern newspapers now painted me as a great danger to the nation, when I was, in my own eyes, a weary and barely competent campaigner. Our tiny “Northern Army” slept on blankets in the woods, ever ready to flee our pursuers. We were sometimes hungry and always fearful, some of us now depleted by the recurring malaria. When my volunteer fighters thought I was out of earshot, they voiced terrible doubts about the violence we had inflicted on supporters of slavery and the future attacks we planned.

Florilla said, “Not a month ago, I witnessed a Lieutenant Iverson driving John Junior and Jason and some other white men shackled like slaves by their ankles. I gave Lieutenant Iverson my mind about this behavior.”

“I would have liked to see that,” I said. “I dare to guess your opinion is etched permanently in Iverson’s mind.”

Florilla smiled. I smiled back. When she was incensed, Florilla could deliver a withering flood of indignation. At earlier times, she had judged our violence against the slavers harshly, and we had been on the receiving end of her criticism. Now, in the emergency, she was quiet on that topic. She recognized the need for armed defense.

“It’s not safe for Fred in camp,” I said. “I want to leave him here with you and Sam. He’ll work his share. He’s good with a plow.”

Florilla knew Fred’s impulsive mounted charge had helped us win the battle at Blackjack, but only at tremendous risk to himself. Like me, Florilla wanted to protect him.

“Fred can stay here now. Sam will accept it.”

We heard another blast from the hunters in the distance.

“Thank you. Thank you very much. This means a great deal to me.”

Florilla nodded. “He’ll probably sleep down the slope in the cabin with Jason and Ellen and Wealthy and the little boys. We’re cramped up here.”

“Fine. That’s perfect.”

“John,” Florilla said. “You know we are scared.”

“I know. I am sorry. When they come, we will be as ready as we can be.”

Florilla nodded gravely, allowing only a hint that my attempt at reassurance had worked. Proslavery forces were rallying in great numbers over the border in Missouri. We would try to protect friends and family here in Osawatomie, but our tiny group was likely to be overrun. Even in defeat, we must make a valiant show of opposition. Our story would be reported in the Eastern newspapers. To win the support of the wealthy and powerful, we must be seen as bold and righteous. We were defending our own. We were also performing for a distant audience, readers who understood little of our agony.

* * *

Owen, my most loyal and steadfast son, greeted me when I arrived at camp alone.

“Fred?” Owen asked.

“He’ll stay with your aunt Florilla and Uncle Sam.”

“Much better. I was worried he’d be running around when the shooting starts.”

“No use worrying,” I said. “God is watching over him. And all of us.”

“Yes, Father. Still…I feel better with him at the Adairs’.”

“As do I.”

Tall Owen, now thirty-one, was the most consistently right-thinking and the boldest of my sons. When others had sometimes lost patience or even mocked Fred for his confusion and weird impulses, Owen had always shown him great care and consideration. I tousled this tall man’s woolly orange hair as I had when he was a boy, and, though visibly embarrassed, he smiled. More than anyone else in the family, Owen had inspired our move to Kansas Territory. Back at our dining table in New York State, he had argued long and hard that our Christian duty required us to put our lives in play in the opposition of slavery.

Owen’s left arm, useless since birth, had kept him from military service and, likely, from marriage. The disability inspired his ferocity. My two eldest, John Junior and Jason, had refused to join in the Pottawatomie attack and hurt me deeply. Fierce Owen had swung his sword boldly and effectively. I trusted Owen completely. I knew he would fight at my side until the end.

Like me, my friends James Cline and Dr. William Updegraff each commanded small militias. We had talked through our plans for the defense these last few days, but I had great doubts, much more than I had let on. Cline, especially, did not inspire confidence. I had heard irreverent talk in his camp, even raw blasphemy. His fighters drank alcohol freely, behavior unthinkable in my camp.

I had more confidence in Updegraff than Cline, but only a little and maybe only because I knew him less well. He seemed a sober and serious man. He had engaged in discussion with us about how to array the forces at some length. Updegraff was no child. Like me, he knew our enemy was unlikely to behave according to our “plans.”

My group was twenty-two volunteers now. Aaron Dwight Stevens was my one true soldier, a big field-smart veteran with a booming voice that others would follow. Aaron had served in the U.S. Army, then been arrested for attacking his own officer. He had escaped from prison and joined up to fight on the free state side. Luke Parsons was another experienced fighter I trusted. Just last week, before he joined us, Luke had taken part in the overrunning and burning of the proslavery fort at Franklin. Many of the rest of our group had experienced violent tangles with the proslavery forces. Several had seen the insides of federal jails. Would they grow cool under fire? We would soon see.

* * *

Shortly after dawn, young nephew Charley rode into our camp, yelling, “They shot Fred dead! We met ’em on the Lawrence Road. Hundreds of ’em. Fred knew the man at the front and called his name, Reverend White. Reverend White shot Fred dead. They shot Mr. Carr and another man. My dad got away into the woods.”

I held, desperate, crying, Charley’s hands. God arrived in my heart like a sliver of the sun inserted into my earthbound body. Such light! Such glory! My volunteers gathered their weapons and readied their mounts.

My body became a column of flame.

* * *

I sent Aaron Stevens and Jason to the west to assess the oncoming force. I hid my fighters behind the trees and brush in the skirting of timber along the Marais des Cygnes River, which ran nearly parallel to the Lawrence Road on the north side.

I put Owen near the front, behind a stone outcrop. With endless practice, he had developed his right arm to great strength. He would aim his rifle well. “Hide here,” I instructed another experienced fighter, indicating a tree stump. “And you, here,” I told another volunteer, pointing out a bush. “Lie down in the grass to stay out of sight.” I placed my other fighters in a long line in the brush from twenty to forty feet apart, hidden in the brambles and the trees. Some found hiding places in the taller grass and behind humps in the land, which allowed them to stand at full height to aim and shoot their rifles.

I was on the northwest with my group. Dr. Updegraff, with his ten militiamen, formed the center, and questionable Captain Cline the east wing of the defending company.

I sent Luke with ten fighters to hold the two-story log fort by the road as long as he could.

Jason ran back and brought me the report. Aaron remained at the front. Reid’s mounted hundreds were coming in two long lines, side by side, towing a wheeled brass cannon. There might have been ten of these uniformed invaders for each of the anxious volunteers on our side.

Cline faced the enemy first, on the road on foot. One of Reid’s mounted slavers shot and killed a militiaman at Cline’s side. Cline and his little army abandoned their dead comrade’s body in the road and fled east, like scattering doves.

Luke soon came back with one other man. “We all got a good look at the oncoming force,” Luke said. “The others…” He opened the fingers of his upturned hand toward the east.

The disappointing performance of these volunteers intensified our emergency and thrust me into the arms of God. I could not linger long in savoring the sacred relationship. Still, I took time to thank God for my increasing serenity, which, experience had taught me repeatedly and well, greatly improved my ability to aim my guns and, even more important, command my fellow fighters with no outward indication of fear.

In my straw hat and tailed coat, with pistols held high in each hand, I walked toward the approaching cavalry in their overwhelming numbers. I did not yet know if Reid’s troops were good fighters, but I saw proof they were dedicated polishers. The glittering of their swords and guns as they approached in the morning sun insulted my eyes in a spectacle I found peculiarly inspiring.

Since we had opened the battle against the slavers in May, I had seen frequent reference to “John Brown” and his activities in the newspapers, some approaching realistic accuracy, some highly embroidered, both to the positive side and to the negative side. James Redpath and Scotsman William A. Phillips promoted me in the New-York Tribune. Richard Hinton wrote Kansas dispatches for the Boston Traveler. I had contributed my own vivid account of our victory at Blackjack to the New-York Tribune.

At the front of our group, I spun around and gave my back to the enemy. I was performing on two stages at once, here, on this rolling prairieland, for the benefit of these volunteers before me, bold or timorous as they might be, and also for the people back East who would soon hear the story of this fight. I needed this world to see me as courageous and forthright and “good.” Maybe this was selfish, even a little silly. But the stories as they appeared in print were indisputably important, vital for my practical purpose. Properly presented tales of moral bravery in battle were key to my next great task: the tugging of money from the wallets of the wealthy.

I directed fire in my clearest, loudest voice.

Not ten yards from me, Owen rose quickly to standing, leveled his rifle, fired, then sank into the yellow grass. I turned and saw a mounted slaver behind me twitch in his saddle. Red appeared on the cursed man’s shirt. He slid and fell under the feet of another man’s horse, which reared frantically and made a terrible whinny.

Another marauder took a bullet from a second of our force, and he, too, crumpled and fell.

The firing grew hotter. The men who had fled returned into position beside and behind me. I welcomed them back with a glance. As I could, I placed each behind a tree or a rock. Confidence flowed in me as a great, warm river. In God’s loving, assuring, humbling company, I walked back and forth in front, encouraging the others, bidding them to aim low and make their fire effective.

All about me, horses reared. Enemy riders fell.

Screams from the slavers cheered me. Along with these misguided supporters of Evil falling and crumpling before me, slavery itself was beginning its long, slow death. I was perhaps alone in my certain Knowledge: our actions today would have great positive effect on the future of our nation and the world. I wanted to tell my comrades, this is it! This is the beginning of the great shift. We are at the front in God’s war!

Some of Reid’s men dismounted, wrestled their cannon into position, and fired a useless blast high into the trees, bringing branches down onto us.

I felt a large bee sting behind my shoulder.

“Have a look here,” I said to Luke, who peeled away a bit of my pierced shirt.

“You’re shot,” Luke said.

“Hah.” I found myself laughing.

Reid ordered his men to dismount and urged them forward. As this huge force approached, our side fell back to the east. We maintained our line and kept shooting, following the riverbank and benefiting from hiding places in the sparse timber. Some waded northward across the river. One of ours was shot and killed in the water. Many were wounded. Many were taken prisoner. Owen and Jason and I and several others edged along the bank until we were out of rifle range of Reid’s men, then waded across in waist-deep water. Aaron and Luke made it across. After this, I did not see Cline or Updegraff.

* * *

Most of Osawatomie’s buildings burned. At dawn, near silence told us the rampage was over. Reid’s army had moved on.

A small group of us waded back across the river to assess the damage and help the survivors. A horrible moan came from within the shell of one still-standing, now roofless cabin. The door was gone. Leather hinges still hung in the doorframe. Inside, lying among clothes and smashed dishes on the dirt floor, I recognized Mr. Carr, a kind and loved neighbor of Florilla and Sam. Carr had a wound as large as a fist under his left ear. He made vocal noises but was unable to speak. He banged his wrists together and pointed at his mouth. Owen gave him a mug of water which he drank wildly, spilling and splashing.

I knew Carr as a righteous man who embodied everything good and true in our young country. Like the rest of us, he had come to Kansas Territory filled with Godly conviction that his presence here would help spread justice and decency. Instead, his life would be stubbed out like the end of a cigar.

Further upslope, we found Florilla and Sam’s cabin still standing and serving as refuge for survivors. Out back, Sam Adair was digging graves. He had dragged several of Reid’s fallen into a neat row in the dirt. He would respect the dead and give proper burial and blessing even to the enemy.

To one side, Fred lay on his back in the dirt. His forehead was pierced and spread garishly, like a cracked egg. His fists were clenched. I kneeled over Fred’s body.

“Lie down flat,” Florilla said, urgently. I obeyed. She raised a rifle. One of Reid’s raiders crawled toward us like a snake, pistol in hand. Florilla shot and killed him.

* * *

The story of this battle at Osawatomie grew quickly, though no journalists had been present, and I never learned which witnesses had reported to which newspaper writers. In brilliant sunlight, “John Brown,” in felt hat and tailed coat, had appeared eight feet tall and marched back and forth in front of the free state volunteers, a pistol in each hand, somehow stepping between rifle shots as Reid’s troops approached. I read these newspaper accounts of myself in wonder and concern. Where would the crazy story go from here?

On a simple provisioning trip to Lawrence, fully shaven now, in my same old felt hat, cotton shirt, and vest, I entered the town meaning only to buy corn and molasses. Someone yelled, “John Brown.” I looked about, considering which way to run to escape any assault. “That’s John Brown,” I heard the man repeat.

People cheered. Some were grinning. One man was waving his hat overhead.

I kept my gaze away from these misinformed, though well-meaning people. The knowledge of so many arranging and rearranging their “story” of John Brown in their minds as they wished to disturbed me greatly. I was unsuited for fame. Indeed, I had found myself unsuited for life in this world in any way.

* * *

In late afternoon, Jason brought stooped and shuddering John Junior into camp. Jason lifted his brother’s ragged shirt, revealing long streaks of scar. Federal authorities, perhaps finally recognizing how completely wrong they had been in blaming the Pottawatomie murders on him (instead of me), had released him. “They staked him like an ox with a chain at his neck, then beat him senseless,” Jason said. “He’s often absent in the mind now. He rarely speaks.” I threw my arms around John Junior and held him close. Tears ran freely down his face and mine. This newly mute man was the best educated of my children, at one time the focus of my highest hopes. Until last spring, he had been a vocal supporter of human rights in the free state legislature and the proud and capable commander of our local militia.

I tried to draw John Junior away from the camp to my prayer spot. I wished we could reach upward together for comfort and support. But John Junior appeared to not comprehend my words. He did not recognize my effort.

Someone or some thing grabbed and knotted my insides above the navel with wicked force. Familiar and awful elements of disease pinched, chilled, and sickened my belly. My tongue tasted like a rotten fish. I recognized the signs of returning malaria. Like most new settlers in the Territory, I had been laid low for weeks at a time in the past, battling disabling fever and chills. The all too familiar agony was beginning again.

I made my way to my prayer space alone and kneeled on the prairie soil. I would present myself nakedly to God, lay bare my confusion and disorder. I had failed badly in my service. I had made countless errors of judgment and tactical intelligence. At least I could catalog my errors and attempt to organize my atonement.

I bowed my head and pressed my palms together. I could not bring order to myself within but, at least right now, I could still exhibit the outward signs of a proper person. Volunteers in the camp were watching my example. For their benefit, I would maintain some appearance of dignity and self-command.

If not for the shameful impiety of such pleading, I might have prayed to be spared a repeat of the affliction. But reasoning prevented me from asking for such a favor. Why should I be spared? Was I especially worthy? Had I made myself in some way more useful to God and His purposes than some other person? Not really. “John Brown” had been pious his whole life, but what good was that? Pious and stupid. Pious and inept. A clod, a bungler. Fancying myself a great moral surgeon, I had led the operation to remove the cancer from the nation’s soul. I had opened the belly and begun the cutting. Then I had lost my way. My Work had shuddered to a shameful impasse. I knew this current path was wrong, but I was not yet able to adjust to the new direction that was needed. I had caused great violence, spread chaos and destruction among the innocent, good-hearted settlers here in Kansas. My Work had led me to abandon my wife and young children hundreds of miles from here, struggling in poverty on the farm with no support from me. My Work had brought about the torture of Jason and John Junior, and driven John Junior to insanity. My Work had killed Fred and many other good and worthy people.

As a boy in Ohio, I had secretly beaten the skin of my back raw with a stick more than once. I reached around and felt a few rough lines of scar from those frenzies.

Pain at my own hands and my own blood dripping from my own broken skin could bring a kind of peace. This was still possible. I could take up a stick and strike my own back. But I rejected such thoughts. I had outgrown such self-abuse. To satisfy God, I had to turn my aggression outward against the Evil of our time. I must attack the flaws of the world, not my own flesh.

I mourned the good person I had meant to be. As a very young man, I had always planned to advance decency and justice in the world. I would embody the ideals of our fearless Savior, love and support all I encountered, fight the moral blight of our society. Instead of this proud and confident Christian warrior, I saw in myself an error-prone, half-wit schemer. Far from making the steady advancement on my God-given plan I intended, I lurched from one harebrained, foredoomed effort to the next.

The pinch of self-judgment released my private demon. The pointy-eared frog monster I called The Specter of Negative Possibilities emerged at my side. The appearance of the diamond-eyed Specter marked the disintegration of my adult personality, my return to infantile helplessness. “Please,” I whimpered. “Please…”

The hideous Specter laughed and sprayed spittle. This laugh echoed the most terrible moments of my life, when the Underworld spoke directly to me and I was falling without apparent limit.

“Help me, oh, God, help me.”

My plea was sincere and heartfelt. But God was stern and silent with me now. No comfort came, no great light, no warmth or cheerfulness. I pressed my face to my hands and cried openly, spilling my tears on the grass and soil.

“Father.” Owen approached.

“My boy.”

“You’re ill.”

“Not only that.”

“You were singing,” Owen said.

“Singing?”

“You were singing very loud,” Owen said.

“I didn’t realize.”

Owen came near, his orange hair discernable in the dusk. I felt my love for him. I welcomed his approach. I needed his help.

“You sing beautifully,” Owen said. “The others appreciate it. I want you to know that. You were singing very sweetly.”

“Thank you, Owen.”

“Will you return to the camp?”

“I can’t just now.”

“Father?”

“What happened to Fred is my fault.”

“You are doing what is needed,” Owen said. His voice shook with devotion.

“The price is too high,” I said.

“We know that cannot be,” Owen said. “God would never permit it.”

Owen was echoing my own words back to me.

“I hope to become a righteous leader like you,” Owen said.

No. Please no.

“I want to inspire the righteous like you.”

No, you don’t want to be like me. No, you don’t.

I looked forward in time to the coming crisis of suffering and destruction. I placed my hand on Owen’s and gave what I meant to be a reassuring grip.

As I rode into the yard beside my troubled son Fred, Florilla Adair, my stern and admirable missionary half-sister, stepped out the cabin door into the morning sunlight holding her axe by the upper shaft, the edges of the blade shiny from fresh sharpening. The Adairs’ blond boy Charley, now twelve, and his little sister Emma grinned at Fred and me. Florilla and Emma each wore a dark blue dress: one full-sized, one tiny. The sight of the bulge at the front of Florilla’s dress ripped my heart. I had passed a rough year here in Kansas since I had last seen my youngest, Ellen, then a baby just approaching her first birthday. Now she was almost two.

In the mess of scrap wood in the yard, I saw the upturned leg of a table and two chair seats. A few weeks before, proslavery terrorists had dragged this furniture out into the yard and smashed it into pieces.

Florilla greeted Fred and me solemnly. “We are glad to see you. I am sorry I can’t invite you in.”

I met Florilla’s extraordinarily steady gaze and knew she and her husband, Sam, had fugitives concealed in the house. We needed to speak no more words about this. Florilla and Sam helped people escape north to freedom. I respected them for their commitment to human decency and for their daring.

A fowling piece fired in the distance. “Sam and Jason, out hunting,” Florilla said.

“Jason! I thought the army still had him in irons.” My sons Jason and John Junior had been arrested for antislavery activity two months before.

Florilla smiled in her subdued way. “Free man now,” she said.

“Thank God.”

She nodded. “For all he’s been through, he seems okay. Delighted to be back with his wife and child.”

“How wonderful! And John Junior?”

“Still in the hands of the federals.”

Officers of the United States Army, in their exasperated state of misplaced rage over our military actions at Pottawatomie, had arrested and tortured John Junior and Jason, who were, in this matter, completely innocent. By our government’s warped logic of crime and innocence at that time, “John Brown” should have been imprisoned and tortured, not my sons. By means of some strange intermixing of rumor and creative newspaper writing, I had become the most public enemy of the beloved institution of slavery. This was silly. I knew what I believed, a rare enough human trait, but I was only one person and a deeply flawed and modest one, at best. You might have thought the foundations of civilization were threatened, the way the proslavery editorialists wailed about our little activities on the borderline between righteousness and evil. It was amusing for me in a strained way, almost funny. Panic in the hearts and minds of the morally corrupt had a certain entertainment value, despite the vast panorama of torment on which this drama played. Above all, they feared losing their “wealth.” So sad.

Southern newspapers now painted me as a great danger to the nation, when I was, in my own eyes, a weary and barely competent campaigner. Our tiny “Northern Army” slept on blankets in the woods, ever ready to flee our pursuers. We were sometimes hungry and always fearful, some of us now depleted by the recurring malaria. When my volunteer fighters thought I was out of earshot, they voiced terrible doubts about the violence we had inflicted on supporters of slavery and the future attacks we planned.

Florilla said, “Not a month ago, I witnessed a Lieutenant Iverson driving John Junior and Jason and some other white men shackled like slaves by their ankles. I gave Lieutenant Iverson my mind about this behavior.”

“I would have liked to see that,” I said. “I dare to guess your opinion is etched permanently in Iverson’s mind.”

Florilla smiled. I smiled back. When she was incensed, Florilla could deliver a withering flood of indignation. At earlier times, she had judged our violence against the slavers harshly, and we had been on the receiving end of her criticism. Now, in the emergency, she was quiet on that topic. She recognized the need for armed defense.

“It’s not safe for Fred in camp,” I said. “I want to leave him here with you and Sam. He’ll work his share. He’s good with a plow.”

Florilla knew Fred’s impulsive mounted charge had helped us win the battle at Blackjack, but only at tremendous risk to himself. Like me, Florilla wanted to protect him.

“Fred can stay here now. Sam will accept it.”

We heard another blast from the hunters in the distance.

“Thank you. Thank you very much. This means a great deal to me.”

Florilla nodded. “He’ll probably sleep down the slope in the cabin with Jason and Ellen and Wealthy and the little boys. We’re cramped up here.”

“Fine. That’s perfect.”

“John,” Florilla said. “You know we are scared.”

“I know. I am sorry. When they come, we will be as ready as we can be.”

Florilla nodded gravely, allowing only a hint that my attempt at reassurance had worked. Proslavery forces were rallying in great numbers over the border in Missouri. We would try to protect friends and family here in Osawatomie, but our tiny group was likely to be overrun. Even in defeat, we must make a valiant show of opposition. Our story would be reported in the Eastern newspapers. To win the support of the wealthy and powerful, we must be seen as bold and righteous. We were defending our own. We were also performing for a distant audience, readers who understood little of our agony.

* * *

Owen, my most loyal and steadfast son, greeted me when I arrived at camp alone.

“Fred?” Owen asked.

“He’ll stay with your aunt Florilla and Uncle Sam.”

“Much better. I was worried he’d be running around when the shooting starts.”

“No use worrying,” I said. “God is watching over him. And all of us.”

“Yes, Father. Still…I feel better with him at the Adairs’.”

“As do I.”

Tall Owen, now thirty-one, was the most consistently right-thinking and the boldest of my sons. When others had sometimes lost patience or even mocked Fred for his confusion and weird impulses, Owen had always shown him great care and consideration. I tousled this tall man’s woolly orange hair as I had when he was a boy, and, though visibly embarrassed, he smiled. More than anyone else in the family, Owen had inspired our move to Kansas Territory. Back at our dining table in New York State, he had argued long and hard that our Christian duty required us to put our lives in play in the opposition of slavery.

Owen’s left arm, useless since birth, had kept him from military service and, likely, from marriage. The disability inspired his ferocity. My two eldest, John Junior and Jason, had refused to join in the Pottawatomie attack and hurt me deeply. Fierce Owen had swung his sword boldly and effectively. I trusted Owen completely. I knew he would fight at my side until the end.

Like me, my friends James Cline and Dr. William Updegraff each commanded small militias. We had talked through our plans for the defense these last few days, but I had great doubts, much more than I had let on. Cline, especially, did not inspire confidence. I had heard irreverent talk in his camp, even raw blasphemy. His fighters drank alcohol freely, behavior unthinkable in my camp.

I had more confidence in Updegraff than Cline, but only a little and maybe only because I knew him less well. He seemed a sober and serious man. He had engaged in discussion with us about how to array the forces at some length. Updegraff was no child. Like me, he knew our enemy was unlikely to behave according to our “plans.”

My group was twenty-two volunteers now. Aaron Dwight Stevens was my one true soldier, a big field-smart veteran with a booming voice that others would follow. Aaron had served in the U.S. Army, then been arrested for attacking his own officer. He had escaped from prison and joined up to fight on the free state side. Luke Parsons was another experienced fighter I trusted. Just last week, before he joined us, Luke had taken part in the overrunning and burning of the proslavery fort at Franklin. Many of the rest of our group had experienced violent tangles with the proslavery forces. Several had seen the insides of federal jails. Would they grow cool under fire? We would soon see.

* * *

Shortly after dawn, young nephew Charley rode into our camp, yelling, “They shot Fred dead! We met ’em on the Lawrence Road. Hundreds of ’em. Fred knew the man at the front and called his name, Reverend White. Reverend White shot Fred dead. They shot Mr. Carr and another man. My dad got away into the woods.”

I held, desperate, crying, Charley’s hands. God arrived in my heart like a sliver of the sun inserted into my earthbound body. Such light! Such glory! My volunteers gathered their weapons and readied their mounts.

My body became a column of flame.

* * *

I sent Aaron Stevens and Jason to the west to assess the oncoming force. I hid my fighters behind the trees and brush in the skirting of timber along the Marais des Cygnes River, which ran nearly parallel to the Lawrence Road on the north side.

I put Owen near the front, behind a stone outcrop. With endless practice, he had developed his right arm to great strength. He would aim his rifle well. “Hide here,” I instructed another experienced fighter, indicating a tree stump. “And you, here,” I told another volunteer, pointing out a bush. “Lie down in the grass to stay out of sight.” I placed my other fighters in a long line in the brush from twenty to forty feet apart, hidden in the brambles and the trees. Some found hiding places in the taller grass and behind humps in the land, which allowed them to stand at full height to aim and shoot their rifles.

I was on the northwest with my group. Dr. Updegraff, with his ten militiamen, formed the center, and questionable Captain Cline the east wing of the defending company.

I sent Luke with ten fighters to hold the two-story log fort by the road as long as he could.

Jason ran back and brought me the report. Aaron remained at the front. Reid’s mounted hundreds were coming in two long lines, side by side, towing a wheeled brass cannon. There might have been ten of these uniformed invaders for each of the anxious volunteers on our side.

Cline faced the enemy first, on the road on foot. One of Reid’s mounted slavers shot and killed a militiaman at Cline’s side. Cline and his little army abandoned their dead comrade’s body in the road and fled east, like scattering doves.

Luke soon came back with one other man. “We all got a good look at the oncoming force,” Luke said. “The others…” He opened the fingers of his upturned hand toward the east.

The disappointing performance of these volunteers intensified our emergency and thrust me into the arms of God. I could not linger long in savoring the sacred relationship. Still, I took time to thank God for my increasing serenity, which, experience had taught me repeatedly and well, greatly improved my ability to aim my guns and, even more important, command my fellow fighters with no outward indication of fear.

In my straw hat and tailed coat, with pistols held high in each hand, I walked toward the approaching cavalry in their overwhelming numbers. I did not yet know if Reid’s troops were good fighters, but I saw proof they were dedicated polishers. The glittering of their swords and guns as they approached in the morning sun insulted my eyes in a spectacle I found peculiarly inspiring.

Since we had opened the battle against the slavers in May, I had seen frequent reference to “John Brown” and his activities in the newspapers, some approaching realistic accuracy, some highly embroidered, both to the positive side and to the negative side. James Redpath and Scotsman William A. Phillips promoted me in the New-York Tribune. Richard Hinton wrote Kansas dispatches for the Boston Traveler. I had contributed my own vivid account of our victory at Blackjack to the New-York Tribune.

At the front of our group, I spun around and gave my back to the enemy. I was performing on two stages at once, here, on this rolling prairieland, for the benefit of these volunteers before me, bold or timorous as they might be, and also for the people back East who would soon hear the story of this fight. I needed this world to see me as courageous and forthright and “good.” Maybe this was selfish, even a little silly. But the stories as they appeared in print were indisputably important, vital for my practical purpose. Properly presented tales of moral bravery in battle were key to my next great task: the tugging of money from the wallets of the wealthy.

I directed fire in my clearest, loudest voice.

Not ten yards from me, Owen rose quickly to standing, leveled his rifle, fired, then sank into the yellow grass. I turned and saw a mounted slaver behind me twitch in his saddle. Red appeared on the cursed man’s shirt. He slid and fell under the feet of another man’s horse, which reared frantically and made a terrible whinny.

Another marauder took a bullet from a second of our force, and he, too, crumpled and fell.

The firing grew hotter. The men who had fled returned into position beside and behind me. I welcomed them back with a glance. As I could, I placed each behind a tree or a rock. Confidence flowed in me as a great, warm river. In God’s loving, assuring, humbling company, I walked back and forth in front, encouraging the others, bidding them to aim low and make their fire effective.

All about me, horses reared. Enemy riders fell.

Screams from the slavers cheered me. Along with these misguided supporters of Evil falling and crumpling before me, slavery itself was beginning its long, slow death. I was perhaps alone in my certain Knowledge: our actions today would have great positive effect on the future of our nation and the world. I wanted to tell my comrades, this is it! This is the beginning of the great shift. We are at the front in God’s war!

Some of Reid’s men dismounted, wrestled their cannon into position, and fired a useless blast high into the trees, bringing branches down onto us.

I felt a large bee sting behind my shoulder.

“Have a look here,” I said to Luke, who peeled away a bit of my pierced shirt.

“You’re shot,” Luke said.

“Hah.” I found myself laughing.

Reid ordered his men to dismount and urged them forward. As this huge force approached, our side fell back to the east. We maintained our line and kept shooting, following the riverbank and benefiting from hiding places in the sparse timber. Some waded northward across the river. One of ours was shot and killed in the water. Many were wounded. Many were taken prisoner. Owen and Jason and I and several others edged along the bank until we were out of rifle range of Reid’s men, then waded across in waist-deep water. Aaron and Luke made it across. After this, I did not see Cline or Updegraff.

* * *

Most of Osawatomie’s buildings burned. At dawn, near silence told us the rampage was over. Reid’s army had moved on.

A small group of us waded back across the river to assess the damage and help the survivors. A horrible moan came from within the shell of one still-standing, now roofless cabin. The door was gone. Leather hinges still hung in the doorframe. Inside, lying among clothes and smashed dishes on the dirt floor, I recognized Mr. Carr, a kind and loved neighbor of Florilla and Sam. Carr had a wound as large as a fist under his left ear. He made vocal noises but was unable to speak. He banged his wrists together and pointed at his mouth. Owen gave him a mug of water which he drank wildly, spilling and splashing.

I knew Carr as a righteous man who embodied everything good and true in our young country. Like the rest of us, he had come to Kansas Territory filled with Godly conviction that his presence here would help spread justice and decency. Instead, his life would be stubbed out like the end of a cigar.

Further upslope, we found Florilla and Sam’s cabin still standing and serving as refuge for survivors. Out back, Sam Adair was digging graves. He had dragged several of Reid’s fallen into a neat row in the dirt. He would respect the dead and give proper burial and blessing even to the enemy.

To one side, Fred lay on his back in the dirt. His forehead was pierced and spread garishly, like a cracked egg. His fists were clenched. I kneeled over Fred’s body.

“Lie down flat,” Florilla said, urgently. I obeyed. She raised a rifle. One of Reid’s raiders crawled toward us like a snake, pistol in hand. Florilla shot and killed him.

* * *

The story of this battle at Osawatomie grew quickly, though no journalists had been present, and I never learned which witnesses had reported to which newspaper writers. In brilliant sunlight, “John Brown,” in felt hat and tailed coat, had appeared eight feet tall and marched back and forth in front of the free state volunteers, a pistol in each hand, somehow stepping between rifle shots as Reid’s troops approached. I read these newspaper accounts of myself in wonder and concern. Where would the crazy story go from here?

On a simple provisioning trip to Lawrence, fully shaven now, in my same old felt hat, cotton shirt, and vest, I entered the town meaning only to buy corn and molasses. Someone yelled, “John Brown.” I looked about, considering which way to run to escape any assault. “That’s John Brown,” I heard the man repeat.

People cheered. Some were grinning. One man was waving his hat overhead.

I kept my gaze away from these misinformed, though well-meaning people. The knowledge of so many arranging and rearranging their “story” of John Brown in their minds as they wished to disturbed me greatly. I was unsuited for fame. Indeed, I had found myself unsuited for life in this world in any way.

* * *

In late afternoon, Jason brought stooped and shuddering John Junior into camp. Jason lifted his brother’s ragged shirt, revealing long streaks of scar. Federal authorities, perhaps finally recognizing how completely wrong they had been in blaming the Pottawatomie murders on him (instead of me), had released him. “They staked him like an ox with a chain at his neck, then beat him senseless,” Jason said. “He’s often absent in the mind now. He rarely speaks.” I threw my arms around John Junior and held him close. Tears ran freely down his face and mine. This newly mute man was the best educated of my children, at one time the focus of my highest hopes. Until last spring, he had been a vocal supporter of human rights in the free state legislature and the proud and capable commander of our local militia.

I tried to draw John Junior away from the camp to my prayer spot. I wished we could reach upward together for comfort and support. But John Junior appeared to not comprehend my words. He did not recognize my effort.

Someone or some thing grabbed and knotted my insides above the navel with wicked force. Familiar and awful elements of disease pinched, chilled, and sickened my belly. My tongue tasted like a rotten fish. I recognized the signs of returning malaria. Like most new settlers in the Territory, I had been laid low for weeks at a time in the past, battling disabling fever and chills. The all too familiar agony was beginning again.

I made my way to my prayer space alone and kneeled on the prairie soil. I would present myself nakedly to God, lay bare my confusion and disorder. I had failed badly in my service. I had made countless errors of judgment and tactical intelligence. At least I could catalog my errors and attempt to organize my atonement.

I bowed my head and pressed my palms together. I could not bring order to myself within but, at least right now, I could still exhibit the outward signs of a proper person. Volunteers in the camp were watching my example. For their benefit, I would maintain some appearance of dignity and self-command.

If not for the shameful impiety of such pleading, I might have prayed to be spared a repeat of the affliction. But reasoning prevented me from asking for such a favor. Why should I be spared? Was I especially worthy? Had I made myself in some way more useful to God and His purposes than some other person? Not really. “John Brown” had been pious his whole life, but what good was that? Pious and stupid. Pious and inept. A clod, a bungler. Fancying myself a great moral surgeon, I had led the operation to remove the cancer from the nation’s soul. I had opened the belly and begun the cutting. Then I had lost my way. My Work had shuddered to a shameful impasse. I knew this current path was wrong, but I was not yet able to adjust to the new direction that was needed. I had caused great violence, spread chaos and destruction among the innocent, good-hearted settlers here in Kansas. My Work had led me to abandon my wife and young children hundreds of miles from here, struggling in poverty on the farm with no support from me. My Work had brought about the torture of Jason and John Junior, and driven John Junior to insanity. My Work had killed Fred and many other good and worthy people.

As a boy in Ohio, I had secretly beaten the skin of my back raw with a stick more than once. I reached around and felt a few rough lines of scar from those frenzies.

Pain at my own hands and my own blood dripping from my own broken skin could bring a kind of peace. This was still possible. I could take up a stick and strike my own back. But I rejected such thoughts. I had outgrown such self-abuse. To satisfy God, I had to turn my aggression outward against the Evil of our time. I must attack the flaws of the world, not my own flesh.

I mourned the good person I had meant to be. As a very young man, I had always planned to advance decency and justice in the world. I would embody the ideals of our fearless Savior, love and support all I encountered, fight the moral blight of our society. Instead of this proud and confident Christian warrior, I saw in myself an error-prone, half-wit schemer. Far from making the steady advancement on my God-given plan I intended, I lurched from one harebrained, foredoomed effort to the next.

The pinch of self-judgment released my private demon. The pointy-eared frog monster I called The Specter of Negative Possibilities emerged at my side. The appearance of the diamond-eyed Specter marked the disintegration of my adult personality, my return to infantile helplessness. “Please,” I whimpered. “Please…”

The hideous Specter laughed and sprayed spittle. This laugh echoed the most terrible moments of my life, when the Underworld spoke directly to me and I was falling without apparent limit.

“Help me, oh, God, help me.”

My plea was sincere and heartfelt. But God was stern and silent with me now. No comfort came, no great light, no warmth or cheerfulness. I pressed my face to my hands and cried openly, spilling my tears on the grass and soil.

“Father.” Owen approached.

“My boy.”

“You’re ill.”

“Not only that.”

“You were singing,” Owen said.

“Singing?”

“You were singing very loud,” Owen said.

“I didn’t realize.”

Owen came near, his orange hair discernable in the dusk. I felt my love for him. I welcomed his approach. I needed his help.

“You sing beautifully,” Owen said. “The others appreciate it. I want you to know that. You were singing very sweetly.”

“Thank you, Owen.”

“Will you return to the camp?”

“I can’t just now.”

“Father?”

“What happened to Fred is my fault.”

“You are doing what is needed,” Owen said. His voice shook with devotion.

“The price is too high,” I said.

“We know that cannot be,” Owen said. “God would never permit it.”

Owen was echoing my own words back to me.

“I hope to become a righteous leader like you,” Owen said.

No. Please no.

“I want to inspire the righteous like you.”

No, you don’t want to be like me. No, you don’t.

I looked forward in time to the coming crisis of suffering and destruction. I placed my hand on Owen’s and gave what I meant to be a reassuring grip.

(Appal)Trad

|

There were no (Appal)Trad poems to share in this is(sue).

|

(Avant)Serial

Avant(Serial): a section dedicated to publishing a novel by chapters in much the same way as novels were published in Dicken's day. Each is(sue) will feature a chapter of an exciting experimental novel - one chapter per is(sue) until the entire novel is thus published. Avant(Serial) will not accept unsolicited manuscripts by submission. Serialised novels in this space will be chosen by joint agreement of all AvantAppal(achia) ed(itors) and will not be Arch(ived). See Sub(missions) for more information.

"Le Overgivers au Club de la Résurrection"

a novel by Jim Meirose, New Jersey

Chapter 7 – Janie At Age Twelve

a novel by Jim Meirose, New Jersey

Chapter 7 – Janie At Age Twelve

About the time Janie Davis turned twelve, and after she had endured another gloomy quiet and superseriously expensive birthday party in the well-fumigated large viewing parlors of the large long wide tall family fourth-generation historic Victorian style over-ginger-breaded baroquely super-ornate gleaming white good-as-new funeral home, she entered into the dead middle of the middle dead middle of the middle school five blocks over from the funeral home to continue her one-rung-at-a-time climb up the maturity ladder and finally gained the common human milestone higher vantage point of seeing the Godlike perfection of her parents gradually spider over with fine cracks, yes until one of the cracks divided open and she could see that their insides did not even closely match what others perceived as their outer clever trickery, when they would say, What, me? No, of course not—no not me. No, I swear on my children I would never lie to you—these the outer actions and outer words they had to maintain the appropriately modeled façade to display to the community, as sooner or later every single person in town and ultimately maybe even the continent or the world, could potentially be customers of theirs. All must pass this way, yes; all must. No one anyplace gets away from finally tapping the town’s or county’s or state’s or nation’s, or etc. etc. etc., finite pack of undertakers. And she took to heart the habit shown above of swearing the truth of everything they said on their children for the lack of handier biblebooks to use. Swear on my children, not the bible, but the children, not my Mother, no, but the children yes; no not; but Janie knew they weren’t really swearing on her like she and any biblebook were interchangeable because they always swore on the children, not the child. And Janie was not children; she was their child. But now pulling out of the empty only dimly remembered deep hole of childhood, it was coming to be for Janie like each moment was another awakening from some continuous dream that was set off by her parents under some covers under some bed in some dark that they would be in multiple times and really could not pinpoint calendar mark commemorate or celebrate with some great loud food drink and loud music all night party, the exact date and time of the lightning bolt miracle of Janie’s conception. As a matter of fact the instant she popped into existence deep in the wet hot dark interior of her Mother, Mother and Father were probably each thinking of nothing but themselves respectively; their separate and very differently designed orgasms pulled their attention from what the real effect of what they were doing in that bed was, and they missed it, d*mn; like staying awake for a three hour late show dying to know the ending but nodding off without noticing it and being unconscious too late to jerk up out of the doze and sleeping soundly through the climax of the movie and never thinking, and this is quite funny, never thinking to ask anyone for the rest of their lives how that movie ended, who lived and who died during the last scenes, as though they had never cared about it at all, or else they were each too ashamed to admit to themselves that they had been so stupid to completely miss seeing and feeling some life event that many think is more important than any other ever. When Janie popped out of the deep child-hole, and the sudden daylight triggered her solar-powered brain to move ahead a half step on the scale of developing consciousness, she brought nothing up from that hole except herself, and the unsettling memory of something having happened to her that had marked her and set her apart forever from the common horde of uncountable others in the same boat both male and female and rich and poor as being somehow special and different and being bound to fulfill some higher destiny she had been assigned, without realizing that each and every other child coming of age into adolescence feels exactly the same way, and each one keeps this belief forever secret deep inside, and thus this mass delusion year after year and generation after generation goes unnoticed; but no, never mind all those millions of others, to each only their own self matters, and Janie like all others felt set apart, marked, selected, and tagged, to experience life on some higher level than any of the others. And this was hammered tightly up in her mind by the fact that she soon noticed once she had left childhood, that there was one thing she had that no one else did that everyone she went to school with considered special and important, and which not a single one of those her age shared; she lived in the gigantic ancient super-historic funeral home on the hill, owned by her parents, and experienced every day the reality of living and eating and sleeping and all, one floor up from an entire moody level of somber soft fragrant dim lit softly caressed by slow organ music from the hidden record player in the wall, that was home to sometimes as many as four or five honest-to-God real life dead people. She was the one who lived in the dead house, yes she was, she was the one that saw dead people every day, and she was the one that whether she liked it or not would go to embalming school and inherit the business in years to come and would spend her whole life in the same huge house she had just come through childhood in, and she would merge down into the unknown, dark, and probably intensely disturbing world of the embalming room, the viewing parlor, and the hordes of grieving black-clad strangers her world would fill to the rim with almost every single day, all rolled up into an unimaginable way of life that would never change until she herself would reach old age and sicken and die and pass through the ghastly dread wall of final death, that pins down life’s end to somewhere, or maybe nowhere; and on this day in question, she sat in the school cafeteria eating lunch with her three and only friends, whose names she promptly forgot upon graduating from middle school to high school, and who are not important enough to be described here anyway; so, as she drained back the final few thimblefuls of remaining chocolate milk from its tiny cow-patterned carton, whose particular brand name is no longer available anywhere on planet Earth, words flowed to her over and down along in the milk flow and she read these words from the brown descending scroll unrolling down before her but that wasn’t really there; they were postmarked as it were from a friend, and they read, So, Janie. How’s the dead people? You check the dead people’s poop-butt temperatures before you came here this morning? Remember, I told you I read in a book you need to do that if you’re an undertaker, because there was crap in those poop-butts so many years that the walls up inside, past the *sshole, permanently contain more than seventy percent of the base elements of the tons of sh*t passed that way. This sh*t-matter lives on in its own secret way even after the loved one is entombed, and can fester up under the right conditions into flaming infections that if the loved one was alive would require mass doses of extra-strength Morphine injected directly into the fiery rimmed beet-red sphincter. These infections can spike up faux-fever in the loved one’s chilly to start with gut, which will cause the corpse to decompose a hundred times faster than it would have otherwise, attracting hordes of flies and other vermin, and in hours it will end up a fucking reeking mess, and all the family lawyers of that loved one, will sue and take your business from you. I know because I read about a case just like that in the paper, in South Africa—there’s laws about that stuff there, you know. They throw crooked undertakers in prison over there—it’s not like here where nobody knows what any undertaker spends his or her time doing in those embalming rooms all day, you know? Maybe sometime you could tell us all about it over lunch. Hey Janie, what you think? Huh Janie? What goes on in the secret room in the basement at your place?

What Sam? Think about what? I wasn’t really listening.

I said how’s the dozen dead people’s sh*tholes? The stiffs stacked up all the time in your house?

Samuel, guess what? sighed Janie.

What?

F*ck you.

Hey, said the blank boy next to Samuel. That’s no way for a lady to talk!

F*ck you too.

Before they reacted, she raised the chocolate milk carton high, blotting them out, and she swore, she swore, for the few seconds they were blotted out it was relatively simple for them to not exist at all; to find out that after all, they never were, except in a dream. The milk taste flooded in and down, the swallow pulling it totally gone worked as good as a new bit of plumbing sucking down waste water should, and just short of Janie smelling that new-home smell, she lowered the drained empty carton and there they were again the three of them reborn. It should not be so easy to switch annoying people in and out of existence so easily, but for Janie it was a game she could play. Then they could say anything good bad or in-between, because they were not really real. Beings easy to switch on and off were not made by the God her parents had taught her to believe in. Beings easy to switch on and off are of the earth or moon, or take your pick anything you can imagine that would be the direct opposite of God. Dog. God. Dog. Goddoggoddoggoddoggod--

The bell yelled lunch away, lunch away, down, and gone; and the Disney knockoff rotating stage revolved and she slid into class for the rest of the afternoon not listening, why the h*ll should she listen, hey, when it makes no difference, because it’s been decided what her remaining sixty or seventy years of life will spend their time doing as she rides happily along atop them, one slow poke year at a time. The class buzzed by, and she must have been in post-shedding her too-small snakeskin shock, because none of her fresh new hide-pores were yet open enough to soak in whatever the teacher had been talking about these last few dozen days. Janie did come to understand one simple thing as she proceeded further into her twelfth year, as the speeding forward dragging invisible moments pulled her along, in a way resembling the way a dredge is pulled along a river bottom, sucking up the mud of knowing new things, too fast too fast really, so her inner spinning double counterweight steam engine style extremely complicated governor apparatus, which had snatched the arms right off many an old-time sleepy night shift steam maintenance man who made the mistake of catching a quick three a.m. doze, leaning over on the slimy slick ten-ton cast iron engine frame where the boss could not see, and without knowing it as the merciful anesthetic sleep covered him, his relaxing arms fell limp into the snappy steel blurry-fast whirl of the governor’s multiple rods pulleys weights all spinning and whipping around, the blood exploded over the cameras that they didn’t have yet back then but you get the picture the blood blocked the cameras because in those days gory live chop them up with old axes and dull kitchen knives films were always destroyed by the police after it had been decided based on them and other hard evidence not to be named but which needed to be kept on ice, and other testimony expert or otherwise including that of the through no fault of their own cr*ppled maintenance laborer, sometimes referred to in Law and Order or Judge Judy reruns as the plaintiff, filtered out every one of the impossible to be remembered facts and details and whatever that flood in onto the developing twelve year old, and get boiled down to the simple knowledge that Janie’s parents were nutty, embarrassing, and nutty; blind, embarrassing, and more and more nutty, and the bag provided for free for her to funnel the accumulation of knowledge into that every twelve year old is issued blew up to bursting and required replacement with more robust models as these simple facts about her parents ballooned into such a giant swirling mass that Janie’s mind protected itself by abandoning the process of bagging up the exponentially increasing knowledge and pushed buttons turned knobs and pulled levers in the control room of her deepest dimmest most elemental lizard-brain, to begin to create words of the expanding mass of pure knowledge, and to have her speak out the facts in thousands of different combinations of words and phrases to her also increasing peer-group, that her parents God bless their hearts, were totally blind, nutty, and embarrassing; and when she shared this she was surprised that this matched the way all of her peers regarded their parents, and so forth; this was the completion of another full circle of her pre-adolescent development. Whew! And this only step one of—too many to come. Growing up is a sonofab*tch! But she had learned to act her age, key to fitting in at school; guys and gals I might be an oddball, guys and gals we might be very different, and in some circumstances a bit different this way or that or off-center in a slightly skewed alternate universe, or we may have been bullying each other this one or that one, leading to totally h*llish high school years, which would then result in fifty years down the road an extraordinarily vengeful cruel-*ssed killing of whoever is handy not necessarily the bully who pushed into the fertile garden hole of the bullied the seed of hatred and the need for revenge but maybe just some sweet newlywed couple half the killer’s age that happen to be strolling before the killer’s dark hole of a hovel because upon investigation in preparation for killing someone sooner or later because of the festering simmering year by year growing raw wound ripped in long ago by the incessant high school bullying; but thank God thank God in Janie’s world no bullying happened because she did exactly the right thing right out of the start of the big fat fabulously posh middle school gate, yes she said to all her new friends upon meeting, Hello hello hello, are you like me? I bet you are like me in that your parents are just like mine in that they are nutty, embarrassing, and blind. So, I think that pretty much equals stupid. Yup, that’s right, what I said. Yes—so. Do we agree on that?

Yes we do new kid.

Yes we do!

New kid.

Yes new kid we do.

So Janie was all set to breeze easily through high school, easy being defined as fitting in with the core of the peer group, and as said easy to divert herself to this and this goal only, because there was really no reason to study or pass or even to pay any attention at all to academics, since her life was all set to follow her parents never have to seek a job never ever be employed never ever, ever, to be in doubt as to which fork in the road to take to be successful safe, well off, and on the easy ride to the top of life eat food everyday a safe private place to p*ss and sh*t plenty of health care coverage a drop in the bucket no yes no nothing sad bad or painful no, so the days went and then, at home, one day Mother Wendy, thank God yes, the smarter of her two parents, or at least the one who still seemed sane, told her; Janie, you need to know—we are taking a trip to Switzerland in a few months. When you were seven or eight, we went to Switzerland—did you like Switzerland? Are you glad we will be going there again? You seemed to have a lot of fun last time. You liked the plane ride. Remember you watched out the window the ocean going by way below and you said to me, clear as a bell, Look at the big pool, Mommy! Look! Down there is a great big pool! I want to go there! Remember, God, I swear, me and your father laughed so hard, you really wanted to go down to the pool! Yes, you did, and after a while you got wound up so tight you cried and cried and you waved across your tray and knocked off all the Play-Doh you were playing with and it was gone and—my God, Janie! You made it such a crazy fun flight! Wild and crazy! Are you glad we’ll be doing it again?