(Issue) 1Avant(Poetry) |

|

"Curation"

S Whitaker, Virginia When I am listening, standing still my neurons are on fire, all or nothing, eyes fixed on some coriaceous juncture of earth and leaf and peachtree, the earthspeak a slow syllable long enough so that I can repose between their language, something to hang a hammock upon and nap between their words. My neurons know this and wish to mirror their slow pause. Cura Cura hee Sha hee sha sha wind in the elms, in the grandfather pines The marsh beyond ss ha ss ha ss ha hoo shu hoo shu The only sound an oyster knows is the sound of its shell cupping the gradual wash of tide over the mud it is buried in. Oh ha, oh ha, oh ha Pull for me the voice of a star uncurling its gases, Ss long silence between Ss snaking out from its hazy corona of hydrogen atoms splitting apart. Ah Sss, Ah Sss, Ah Sss, not a snake but gas slipping out of gravity. A muted push of force, a wooden blade wuffling as a samurai swings his practice sword under the bow of a paper lantern tree. Ah ha Ah ha breath breath Breath |

Avant(Art)

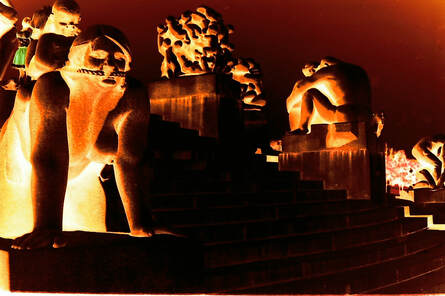

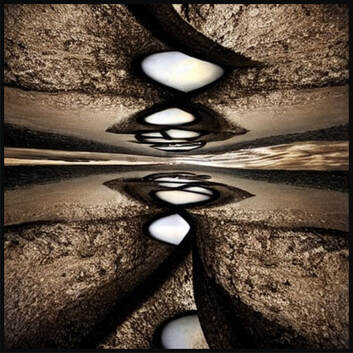

"The Decisive Embrace of Light and Snow"

Bill Wolak, New Jersey

Bill Wolak, New Jersey

Avant(Story)

"Divine" Part 1

Rudy Thomas, Kentucky

The Hour of Worship Radio Program

As he had promised the woman he would do, my uncle turned on the radio as he drove us home.

“Now, we shall hear a song. I believe Sister Mary Magdalean and her quartet are ready. They’re gathered round the microphone. What song have you picked out for us today, Sister?”

“What a friend we have in Jesus,” she answered.

“That’s a good old one, radio listeners. Remember now, the only way we can keep this radio program coming to you is for you to send us your love offering. If you love God...”

“I love God,” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“God bless you, Sister. The Lord Jesus said he has gone to prepare a place for you that where he is you might be also. Dearly beloved, you listeners there at home, if you want to help us spread the Gospel over the air....just imagine what Jesus could have done with this marvel...”

“Brother House, me and the boys here have taken up a love offering and we’d be pleased if you’d take it now.”

“God bless you again, Sister and you boys. For you, listeners, out there in radio land, friends, let that be an example for you. Send your love offerings to me: Preacher House, Post Office Box 333, Divine... Besides his twelve chosen disciples, there were women Jesus had cured of different diseases that followed him around...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“One was Mary Magdalean. If you remember, she was the one with seven evil spirits that he cast out...”

“Amen, Preacher!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted. “Praise be to him...”

Another was Joanna, the wife of a nobleman named Chuza. He was a high officer in the court of King Herod, the ruler of Galilee. Another was named Susanna, and there were a number of other women. The point I’m trying to make is that some of these women were rich, and gave freely of their money to help Jesus. I don’t think Sister Mary Magdalene here is rich...”

“Amen! No, Preacher!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted, bumping the microphone.

“All the four gospels agree in saying that the first person to see Jesus Christ after his death on that cruel cross was Mary Magdalean, that is Mary of Magdala, the woman a year before or thereabout he had driven out evil spirits from her, and who in love for what...”

“Amen, Preacher, I love the Lord...”

“God bless you sister as your namesake was blessed. As I was saying, she followed him and helped him with her gifts, for she was a rich woman. None of us in this studio is rich, but we love him, too...”

“Amen, Preacher, I sure do,” Sister Mary Magdalene called out...

“Now, out there in radio land, stop whatever it is you’re doing and listen to this fine quartet sing for you. After they’re done, fix up a love offering. If we’re going to be able to work for him in our radio ministry, we need more of you to be our disciples...”

“Amen! Amen!”

The quartet sang; my uncle drove, gravel from the road pinging the rocker panels of his car, but we did not get to hear Preacher House deliver his sermon, for my uncle had turned into our driveway as he was praising the singers and asking for all who loved such gospel songs to send their love offerings...

Love Offering

I was at the Divine Post Office with my father, my brother, and my older sister, older by fifteen months, and the postmaster was talking about the Divine Hour of Worship radio program when Brother House walked in...

"How are you, Brother House?" father asked.

"I'm fine, Red," he answered.

Red was father's nickname, one of several.

"It was good to see your sister and her husband last Sunday," Brother House began...

"They said they saw you," father said.

I remember what my uncle had said when we passed Brother House. It surprised me that the man spoke now as though he and my uncle had taken time to talk...

"And these are yours?" Brother House asked, pointing at the three of us.

"Two of them, at least," Father laughed.

"I see," Brother House said, looking at us for a moment. "Red hair and freckles..."

Father always used that two of them, at least, line when he introduced us to strangers.

"The other one?"

I knew what was coming next: he always used the line about how the hospital mixed me up with another man's baby in the nursery before a nurse brought me into the hospital room where he and my mother were...

"I think he belongs to a traveling salesman," father said.

My sister and my brother laughed. I felt my face flush...

"Let's see, now," Brother House rubbed his chin. "Only traveling salesman in these parts is the Watkins’ man..."

"We were living in Ohio when he was born," father said. "They've got a sh** load; pardon my French, of traveling salesmen up there..."

"Dayton?" Brother House asked.

"Springfield," father said.

"You've a sister in Dayton, don't you?"

"I sure do and one in Sherwood..."

"I know where Cincinnati, Dayton, and Sherwood are, but I can't place Springfield."

"It's north and east of Cincinnati..."

"I see. These young 'uns went to church last Sunday. You should be proud of them..."

"They all seem to be smarter than I am," father laughed.

"The older boy there found the prize egg. Won a silver dollar..."

"You did, did you?" Brother House asked, turning to face me.

I nodded; still embarrassed from the ribbing I had taken.

"What can I do for you, Brother House?" the postmaster asked.

"I thought I might best pick up my mail," Brother House said.

"Don't think you've got any," the postmaster said, "but I'll check."

"Did you two happen to catch my radio program last Sunday?" Brother House asked.

"No," father answered. "Didn't know you were on the radio..."

"Me neither," the postmaster, the grandson who was filling in for the woman normally in charge of the Divine Post Office, said, turning around to face Brother House. "No mail for you..."

Brother House looked disappointed...

"We heard you," my sister said.

Brother House turned toward us.

"We did!" my brother said.

"Most of it," I said. "We got home before it was over."

"Out of the mouths of babes," Brother House said, smiling at us.

"What's the name of this radio program?" the postmaster asked.

"The Divine Hour of Worship," Brother House answered.

"I thought there might be a love offering or two for me."

"Nope," the postmaster said. "Nothing..."

Brother House was about the saddest looking man I had ever seen. He turned without saying anything else and started toward the door...

"What did you say you call your radio program?"

"The Divine Hour of Worship," Brother House replied, turning past us to face the postmaster again.

"There's a package here with that name on it," the postmaster said. "I didn't know what to do with it. I put in the outgoing mail with a label, return to sender. I'll get it for you."

Brother House perked up noticeably. I was happy for him, thinking how he must feel about a love offering so big it would come in a package. The postmaster was gone for a few minutes before he came back to the counter and slid the package beneath the bars toward Brother House. The young man took it and began to rip off the brown paper, grocery bag wrapping.

I looked a father. He had a possum grin on his face. The young postmaster was about to choke, trying to keep from laughing too.

"How much offering did you get?" father asked.

Brother House turned to face him and the postmaster walked toward the back, laughing so hard inside that his head and shoulders bounced.

Brother House rubbed his chin. Father had a serious look on his face. Brother House tossed him the book. Father caught it. The stand in postmaster returned to the caged counter, composed and professional looking again.

Father opened the book and began to read: "Timely Sermons by Dainel Rosoff. Do you reckon they misspelled his name? Reckon they meant Daniel Roseoff? Copyright 1936... Well, look at that! Man signed his name. D-a-i-n-e-l R-o-s-o-f-f... Wrote: First Edition under that... Wrote: For Brother House. Lift up thy voice with joy. You've got a collector's item here, Brother House. You best take care of it. Might be worth a hundred bucks one of these days..."

"I bet the man was traveling through here and heard you, Brother House. Give him back that book, Mr. Red!"

Father got up and walked over to Brother House. Brother House took the book, but there was no joy on his face.

"Do you sing on your program?" the postmaster asked.

"Sister Mary Magdalene and her band sing," Brother House said.

"And you don't sing?" Father asked.

"I can't carry a tune for shinola," Brother House answered. "I bring the message..."

"What message you bringing this Sunday, Brother House?" the postmaster asked.

"The Lord ain't laid a sermon on me yet."

"Well, Brother House, this government work don't pay much or I'd give you a love offering” the postmaster said.

"I would, too, Brother House, but I've not been back from Indiana long enough to get a job yet. I've farming some, but you know that's a one time a year prospect where money's concerned..."

"I do. I didn't ask you boys for a love offering. Red, I know you got these three young 'uns to feed. Where was it in Indiana that you were? New Castle?"

"Yeah... I had a job at Chrysler, but they closed the doors. That's why I moved back here. I hear they’ve kept a few old timers working..."

"I tell you what, Brother House," the postmaster said...

"What?"

"Maybe we can help you with your sermon just in case the Lord's laying sermons on all them other preachers in this world for Sunday. I think you need to preach on the sins that lead young men like me astray here in the Divine Community. What do you think, Mr. Red?"

"I think you're on to something...H-m-m-m... What about smoking?" father asked.

I saw the young postmaster frown and push his pack of Camel cigarettes out of sight.

"Is smoking a sin?" the postmaster asked. "Are you a Nazarene, Brother House?"

"I think anything worldly can be a sin," Brother House said, not answering the postmaster's second question.

"What about drinking, Brother House? Surely you can preach against that!"

I saw father frown.

"Drinking has led many a young man down the path of destruction," Brother House said.

"And what about Jezebels’?" father asked.

"That's right," the postmaster said. "What about the women who have been married three of four times and tempt so as to take us young men down..."

"I see," Brother House interrupted. "Lead our young men down the road of sin. You have ... I mean, I think you boys have touched the Lord. I feel him moving me to do that for you. You listen tomorrow. I know the Lord will have me say what you want..."

"I'll listen," father said. "I'll get everybody I can to listen."

"Me, too," the postmaster said. "And you'll get a love offering for it... Just you wait and see..."

Father was grinning. The postmaster was grinning and Brother House did not look sad any more.

It seemed like the right thing to do. I reached into my pocket and took out my silver dollar. I walked over to Brother House and placed it in his hand. He tucked his book under his arm and left the Divine Post Office without even thanking me.

The Sermon

"I'm taking you with me," father said as we walked from the barn toward the house on Sunday morning.

I never asked him where he was taking me. I was just happy for the invitation.

"We'll leave about eleven," he said.

I didn't mention anything to my sister and my brother, for I knew father would invite them, too, if he were to take them. The three of us spent the morning in the shed above the cellar, watching the water level slowly reside, flowing through a half inch plastic pipe. Now and then, we would leave the shed, crawl under the barb-wire fence, and run down the hillside pasture to the end of the hose to see if the dingy water had stopped flowing. During the warming, April night, a storm hit and rain fell until after sunrise. Father had not siphoned the water to get it draining. He had plugged the end inside the shed with a cork from a wine bottle and had climbed a ladder to get on the roof where he sat with a funnel in the other end. Mother carried water, two lard buckets at a time and tied one to the rope that father dropped. He would pull the bucket up, take the lid off, pour the water into the hose, and then drop the bucket and lid to pull up the second. When the pipe was filled to overflowing, he put another cork in it, dropped it and climbed down.

"Take it over the hill," he told mother, "and when I tell you, jerk that cork out..."

I followed father and my brother and sister went with mother. I watched him hold the pipe in his right hand until mother almost tugged it away.

"Now!" he shouted.

I ran to the fence.

"Now!" I shouted.

"Now!" shouted my brother who was half-way between the fence and our mother and sister.

"Now!" shouted my sister, standing next to mother.

It was a smooth operation, but by eleven, less than three foot of water had emptied from the large cellar. While my sister and brother rode the brindle cow in the pasture, I sat on the front porch.

"Ready?" father asked when he came out of the house.

"Yes, sir!" I could not contain my excitement when I answered.

I did not know where we were going until father turned left into the parking lot at Oleman Rains' store. I walked behind him as we crossed the gravels. The store, a white, one-room frame and clapboard building with a deck across the front and six steps leading up on the right, was a community center as well as a country store.

Inside the store, the postmaster and three other men I had seen before, but I did not know by name, played Rook. Two other men leaned on the counter, talking to Oleman who seldom ran the store, leaving that task to his wife and daughters while he operated the farm or hauled livestock to area stock yards.

"You made it," Oleman called out.

"Told you I'd be here," father said.

"Who you got with you?" Oleman asked, but I knew he knew who I was.

What father said surprised me...

"My son," he answered. "Give him a Baby Ruth and a Dr. Pepper even though it ain't ten, two, or four..."

Oleman grabbed a candy bar and I started to take it...

"Not that one," father told the postmaster. "He deserves that big one you've got hid on that shelf behind you."

Oleman turned, picked up the giant candy bar, and gave it to me.

"You know where the drinks are, Red. Get him one. What can I get you?"

"Baloney sandwich," father answered.

Oleman turned toward his left then turned right at the meat case. He took out the rolled balogna and thick-sliced it with a butcher knife.

"What's you want on it?"

"A slab of cheese and a tomato," father said.

"No pickles?"

"No pickles," father said, handing me a bottle of Dr. Pepper.

"She's here," someone called.

I turned around and discovered that the she in question was Sister Mary Magdalene.

“You’re gonna be late for the radio show, Sister,” father said.

“No, no...” Mary Magdalene smiled. “Be right on time. Don’t want to be sitting out front like I have to do when I go to the doctor’s office. I want to get there when it’s time to walk down the hall to the studio and the DJ turns on the On The Air sign. Need me a Pepsi...”

“Got a frosty one just like you want it,” Oleman said as he walked toward the General Electric refrigerator. He took a bottle from the top shelf with difficulty, for I could see it was stuck to the side of the ice-covered wall of the freezer compartment.

“How are you, young man?” she asked, mussing my hair with her left hand while he extended her right toward Oleman.

“Keep your money, Sister,” father said.

Oleman’s chin dropped.

“Oleman’s matching the silver dollar the boy gave Brother House for a love offering. Same dollar he got for finding the prize egg at church...”

“Lawdy be,” Sister Mary said, mussing my hair again. “I put up that dollar. I’ll give that old hoot Oelman’s dollar bill and get that silver dollar back for you, son.”

Before I could tell her not to, she began to speak quickly...

“Coloring Easter eggs is a fun Easter tradition. Nowadays, it’s become an art form. They sell many different kits for it. Coloring Easter eggs is only one of the traditions surrounding eggs on Easter. Parents tell their babies how the Easter Bunny hides the eggs, and them babies go on an Easter egg hunt...”

“I saw the Easter bunny this year for the first time in my life,” Oleman said. “Black and white flop-eared bunny it was. It weren’t no white rabbit like Alice followed and it weren’t no wild, brown rabbit like me and Cameron hunt...”

Sister Mary stared him down then continued...

“Every year I color eggs the same way. I'm good at coloring Easter eggs without a kit, with food coloring and natural dyes like my Mama taught us kids to do it. You color eggs, boy?”

“Yes’m,” I answered.

“Good for you... Do you know who started the tradition?”

“Your namesake,” father said.

“Well I’ll be John Brown, old boy, you do know don’t you. Mary Magdalene was a woman of some wealth and social status. Following Jesus Christ's death and resurrection, she used her position to gain an invitation to a banquet given by Emperor Tiberius Caesar. When she met him, she held a plain egg in her hand and exclaimed Christ is risen! Caesar laughed, and said that Christ rising from the dead was as likely as the egg in her hand turning red while she held it. Before he finished speaking, the egg in her hand turned a bright red, and she continued proclaiming the Gospel to the entire imperial house. Is that how you heard it?”

“Only thing I remember about it is that she was the one started it...”

“I gotta run, boys. You all listening to the program today?”

“Got a bunch of the men folk coming in atterwhile, Sister,” Oleman said. “We wouldn’t miss it for the world...”

“Bless your heart, old boy,” Sister Mary Magdalene said, smiled, and then rushed from the country store.

Men from Divine Ridge began to arrive a few minutes before nine o’clock. Most of them I knew by name. The couple I did not know I would ask my father about later.

Before Oleman finished ringing up their purchases, he turned on the radio, full blast.

“Good morning out there in radio land, dear hearts,” Brother House’s voice silenced the crowd that had gathered. “Sister Mary Magdalene and her quartet will sing for you now. What’s you got for us today, Sister?”

“We’re gonna try two songs: In the Garden and Bearing the Cross to Win the Crown. These are going out to Oleman and Red and all the boys down Divine Ridge community way. Key of C...”

A shout,” Amen,” went up from Oleman...

“You boys oughta be ashamed now,” Jason laughed. “Woman should kill you two...”

I didn’t know why he said that.

“Shut up and listen,” Oleman shouted.

“I’ll thank her next time I see her,” father said of Sister Mary Magdalene and her group. “They keep it up; they’ll be good before you know it.”

After the two songs, Brother House began to speak: “A- man! Good job sister... All you listeners take the messages from them fine songs to heart and send us your love offerings so we can keep this radio program going...”

“Any lover offerings this week?” Sister Mary Magdalene’s voice rang out...

“Nary a one,” Brother House said.

Oleman and father looked at me. I dropped my head.

“Blessed be all of you out there in radio land. Before our time is up, I want to say what God has laid on my heart. He has told me that I should speak to the young men out there in radio land. If you have a young man in your house, get him in front of the radio so he can hear this. It will be a blessing today...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted...

“The Lord God has told me that this world is full of temptations for everyone, but he has told me; bless his name, to speak to every young man out there listening this fine day... Let us pray...”

“Good, Lord,” Sister Mary Magdalene prayed. “We thank you for this beautiful morning you have allowed us to gather here in your presence. Go with us throughout the rest of this worship service and bless Brother House for being your instrument. We thank you for the young men gathered around the radio and we pray they get a blessing out of this message. We pray in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen...”

“A-man, Sister, hallelujah, a-man... You know, dear hearts, the Lord has laid it upon me to tell you young boys out there that the Devil tempts you with cigarettes. The Devil wants you to think smoking is fun. Well, it ain’t. Your body is a temple so the Good Book tells us...”

“Amen, Brother House... My body is a temple unto the Lord. I never smoked in my life. You young boys heed the message Brother House is giving you...” Sister Mary Magdalene interrupted.

“The Devil knows your heart, young man, whoever you are out there in radio land. He can read it like the Lord can. He reads it to work his own no good on you. I tell you young men in the radio audience, the Devil ain’t never up to no good. Give up them smokes and give yourself to God...”

“Amen and amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted in the background.

“And I tell you what the Lord told me just yesterday, young men out there in Divine Ridge and every other ridge and holler in this county, sons, don’t take to drink neither... Now I’m not talking about water or pop, them kind of drinks. I’m telling you the Lord don’t approve of beer, homebrew, and likker of all kinds. Young man gets imbibed, he defiles his body.”

“Red, he didn’t say anything about taking a little wine for the stomach’s sake, did he?”

“No, he didn’t, Oleman, bless his heart...”

A roar went up in the store that drowned out Sister Mary Magdalene’s amens...

“Now we’re getting close on time here, dear hearts out there in radio land. Before we go, I want to remind you to get those love offerings in the mail... Send your love offerings to me: Preacher House, Post Office Box 333, Divine...”

“He ain’t gonna do it,” Oleman cried out. “You sure you and Mrs. Mooringson’s grandson primed him about Jezebels?”

“I heard them,” I said.

“Maybe he will do it yet,” Father said.

“Before we sign off, brothers and sisters, and all you young men out there, let me tell you that the Devil is at work. He wants you to believe smoking and drinking is fun...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“And I think we have just enough time...”

“He’s gonna do it,” father called out, looking toward me.

“The Devil works his way through Jezebels out there in the world, women who have been married three or four time and prey on our young men like mantis on flies. Young men, I’m telling you the Lord don’t approve of them painted hussies that lure you down the road of sin...”

There was silence on the radio...

After a moment, Brother House returned to his sermon...

“I said the Good Lord don’t want you young men out there within the sound of my voice to be sinning, lusting after no painted Jezebels..."

There was a longer silence...

Brother House cleared his throat...

More silence...

“I see that met with a cold reception,” Brother House cleared his voice again. “Get your love offerings in the mail, dear hearts, and we’ll be back on the air next Sunday, God willing...”

"Divine" Part 1

Rudy Thomas, Kentucky

The Hour of Worship Radio Program

As he had promised the woman he would do, my uncle turned on the radio as he drove us home.

“Now, we shall hear a song. I believe Sister Mary Magdalean and her quartet are ready. They’re gathered round the microphone. What song have you picked out for us today, Sister?”

“What a friend we have in Jesus,” she answered.

“That’s a good old one, radio listeners. Remember now, the only way we can keep this radio program coming to you is for you to send us your love offering. If you love God...”

“I love God,” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“God bless you, Sister. The Lord Jesus said he has gone to prepare a place for you that where he is you might be also. Dearly beloved, you listeners there at home, if you want to help us spread the Gospel over the air....just imagine what Jesus could have done with this marvel...”

“Brother House, me and the boys here have taken up a love offering and we’d be pleased if you’d take it now.”

“God bless you again, Sister and you boys. For you, listeners, out there in radio land, friends, let that be an example for you. Send your love offerings to me: Preacher House, Post Office Box 333, Divine... Besides his twelve chosen disciples, there were women Jesus had cured of different diseases that followed him around...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“One was Mary Magdalean. If you remember, she was the one with seven evil spirits that he cast out...”

“Amen, Preacher!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted. “Praise be to him...”

Another was Joanna, the wife of a nobleman named Chuza. He was a high officer in the court of King Herod, the ruler of Galilee. Another was named Susanna, and there were a number of other women. The point I’m trying to make is that some of these women were rich, and gave freely of their money to help Jesus. I don’t think Sister Mary Magdalene here is rich...”

“Amen! No, Preacher!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted, bumping the microphone.

“All the four gospels agree in saying that the first person to see Jesus Christ after his death on that cruel cross was Mary Magdalean, that is Mary of Magdala, the woman a year before or thereabout he had driven out evil spirits from her, and who in love for what...”

“Amen, Preacher, I love the Lord...”

“God bless you sister as your namesake was blessed. As I was saying, she followed him and helped him with her gifts, for she was a rich woman. None of us in this studio is rich, but we love him, too...”

“Amen, Preacher, I sure do,” Sister Mary Magdalene called out...

“Now, out there in radio land, stop whatever it is you’re doing and listen to this fine quartet sing for you. After they’re done, fix up a love offering. If we’re going to be able to work for him in our radio ministry, we need more of you to be our disciples...”

“Amen! Amen!”

The quartet sang; my uncle drove, gravel from the road pinging the rocker panels of his car, but we did not get to hear Preacher House deliver his sermon, for my uncle had turned into our driveway as he was praising the singers and asking for all who loved such gospel songs to send their love offerings...

Love Offering

I was at the Divine Post Office with my father, my brother, and my older sister, older by fifteen months, and the postmaster was talking about the Divine Hour of Worship radio program when Brother House walked in...

"How are you, Brother House?" father asked.

"I'm fine, Red," he answered.

Red was father's nickname, one of several.

"It was good to see your sister and her husband last Sunday," Brother House began...

"They said they saw you," father said.

I remember what my uncle had said when we passed Brother House. It surprised me that the man spoke now as though he and my uncle had taken time to talk...

"And these are yours?" Brother House asked, pointing at the three of us.

"Two of them, at least," Father laughed.

"I see," Brother House said, looking at us for a moment. "Red hair and freckles..."

Father always used that two of them, at least, line when he introduced us to strangers.

"The other one?"

I knew what was coming next: he always used the line about how the hospital mixed me up with another man's baby in the nursery before a nurse brought me into the hospital room where he and my mother were...

"I think he belongs to a traveling salesman," father said.

My sister and my brother laughed. I felt my face flush...

"Let's see, now," Brother House rubbed his chin. "Only traveling salesman in these parts is the Watkins’ man..."

"We were living in Ohio when he was born," father said. "They've got a sh** load; pardon my French, of traveling salesmen up there..."

"Dayton?" Brother House asked.

"Springfield," father said.

"You've a sister in Dayton, don't you?"

"I sure do and one in Sherwood..."

"I know where Cincinnati, Dayton, and Sherwood are, but I can't place Springfield."

"It's north and east of Cincinnati..."

"I see. These young 'uns went to church last Sunday. You should be proud of them..."

"They all seem to be smarter than I am," father laughed.

"The older boy there found the prize egg. Won a silver dollar..."

"You did, did you?" Brother House asked, turning to face me.

I nodded; still embarrassed from the ribbing I had taken.

"What can I do for you, Brother House?" the postmaster asked.

"I thought I might best pick up my mail," Brother House said.

"Don't think you've got any," the postmaster said, "but I'll check."

"Did you two happen to catch my radio program last Sunday?" Brother House asked.

"No," father answered. "Didn't know you were on the radio..."

"Me neither," the postmaster, the grandson who was filling in for the woman normally in charge of the Divine Post Office, said, turning around to face Brother House. "No mail for you..."

Brother House looked disappointed...

"We heard you," my sister said.

Brother House turned toward us.

"We did!" my brother said.

"Most of it," I said. "We got home before it was over."

"Out of the mouths of babes," Brother House said, smiling at us.

"What's the name of this radio program?" the postmaster asked.

"The Divine Hour of Worship," Brother House answered.

"I thought there might be a love offering or two for me."

"Nope," the postmaster said. "Nothing..."

Brother House was about the saddest looking man I had ever seen. He turned without saying anything else and started toward the door...

"What did you say you call your radio program?"

"The Divine Hour of Worship," Brother House replied, turning past us to face the postmaster again.

"There's a package here with that name on it," the postmaster said. "I didn't know what to do with it. I put in the outgoing mail with a label, return to sender. I'll get it for you."

Brother House perked up noticeably. I was happy for him, thinking how he must feel about a love offering so big it would come in a package. The postmaster was gone for a few minutes before he came back to the counter and slid the package beneath the bars toward Brother House. The young man took it and began to rip off the brown paper, grocery bag wrapping.

I looked a father. He had a possum grin on his face. The young postmaster was about to choke, trying to keep from laughing too.

"How much offering did you get?" father asked.

Brother House turned to face him and the postmaster walked toward the back, laughing so hard inside that his head and shoulders bounced.

Brother House rubbed his chin. Father had a serious look on his face. Brother House tossed him the book. Father caught it. The stand in postmaster returned to the caged counter, composed and professional looking again.

Father opened the book and began to read: "Timely Sermons by Dainel Rosoff. Do you reckon they misspelled his name? Reckon they meant Daniel Roseoff? Copyright 1936... Well, look at that! Man signed his name. D-a-i-n-e-l R-o-s-o-f-f... Wrote: First Edition under that... Wrote: For Brother House. Lift up thy voice with joy. You've got a collector's item here, Brother House. You best take care of it. Might be worth a hundred bucks one of these days..."

"I bet the man was traveling through here and heard you, Brother House. Give him back that book, Mr. Red!"

Father got up and walked over to Brother House. Brother House took the book, but there was no joy on his face.

"Do you sing on your program?" the postmaster asked.

"Sister Mary Magdalene and her band sing," Brother House said.

"And you don't sing?" Father asked.

"I can't carry a tune for shinola," Brother House answered. "I bring the message..."

"What message you bringing this Sunday, Brother House?" the postmaster asked.

"The Lord ain't laid a sermon on me yet."

"Well, Brother House, this government work don't pay much or I'd give you a love offering” the postmaster said.

"I would, too, Brother House, but I've not been back from Indiana long enough to get a job yet. I've farming some, but you know that's a one time a year prospect where money's concerned..."

"I do. I didn't ask you boys for a love offering. Red, I know you got these three young 'uns to feed. Where was it in Indiana that you were? New Castle?"

"Yeah... I had a job at Chrysler, but they closed the doors. That's why I moved back here. I hear they’ve kept a few old timers working..."

"I tell you what, Brother House," the postmaster said...

"What?"

"Maybe we can help you with your sermon just in case the Lord's laying sermons on all them other preachers in this world for Sunday. I think you need to preach on the sins that lead young men like me astray here in the Divine Community. What do you think, Mr. Red?"

"I think you're on to something...H-m-m-m... What about smoking?" father asked.

I saw the young postmaster frown and push his pack of Camel cigarettes out of sight.

"Is smoking a sin?" the postmaster asked. "Are you a Nazarene, Brother House?"

"I think anything worldly can be a sin," Brother House said, not answering the postmaster's second question.

"What about drinking, Brother House? Surely you can preach against that!"

I saw father frown.

"Drinking has led many a young man down the path of destruction," Brother House said.

"And what about Jezebels’?" father asked.

"That's right," the postmaster said. "What about the women who have been married three of four times and tempt so as to take us young men down..."

"I see," Brother House interrupted. "Lead our young men down the road of sin. You have ... I mean, I think you boys have touched the Lord. I feel him moving me to do that for you. You listen tomorrow. I know the Lord will have me say what you want..."

"I'll listen," father said. "I'll get everybody I can to listen."

"Me, too," the postmaster said. "And you'll get a love offering for it... Just you wait and see..."

Father was grinning. The postmaster was grinning and Brother House did not look sad any more.

It seemed like the right thing to do. I reached into my pocket and took out my silver dollar. I walked over to Brother House and placed it in his hand. He tucked his book under his arm and left the Divine Post Office without even thanking me.

The Sermon

"I'm taking you with me," father said as we walked from the barn toward the house on Sunday morning.

I never asked him where he was taking me. I was just happy for the invitation.

"We'll leave about eleven," he said.

I didn't mention anything to my sister and my brother, for I knew father would invite them, too, if he were to take them. The three of us spent the morning in the shed above the cellar, watching the water level slowly reside, flowing through a half inch plastic pipe. Now and then, we would leave the shed, crawl under the barb-wire fence, and run down the hillside pasture to the end of the hose to see if the dingy water had stopped flowing. During the warming, April night, a storm hit and rain fell until after sunrise. Father had not siphoned the water to get it draining. He had plugged the end inside the shed with a cork from a wine bottle and had climbed a ladder to get on the roof where he sat with a funnel in the other end. Mother carried water, two lard buckets at a time and tied one to the rope that father dropped. He would pull the bucket up, take the lid off, pour the water into the hose, and then drop the bucket and lid to pull up the second. When the pipe was filled to overflowing, he put another cork in it, dropped it and climbed down.

"Take it over the hill," he told mother, "and when I tell you, jerk that cork out..."

I followed father and my brother and sister went with mother. I watched him hold the pipe in his right hand until mother almost tugged it away.

"Now!" he shouted.

I ran to the fence.

"Now!" I shouted.

"Now!" shouted my brother who was half-way between the fence and our mother and sister.

"Now!" shouted my sister, standing next to mother.

It was a smooth operation, but by eleven, less than three foot of water had emptied from the large cellar. While my sister and brother rode the brindle cow in the pasture, I sat on the front porch.

"Ready?" father asked when he came out of the house.

"Yes, sir!" I could not contain my excitement when I answered.

I did not know where we were going until father turned left into the parking lot at Oleman Rains' store. I walked behind him as we crossed the gravels. The store, a white, one-room frame and clapboard building with a deck across the front and six steps leading up on the right, was a community center as well as a country store.

Inside the store, the postmaster and three other men I had seen before, but I did not know by name, played Rook. Two other men leaned on the counter, talking to Oleman who seldom ran the store, leaving that task to his wife and daughters while he operated the farm or hauled livestock to area stock yards.

"You made it," Oleman called out.

"Told you I'd be here," father said.

"Who you got with you?" Oleman asked, but I knew he knew who I was.

What father said surprised me...

"My son," he answered. "Give him a Baby Ruth and a Dr. Pepper even though it ain't ten, two, or four..."

Oleman grabbed a candy bar and I started to take it...

"Not that one," father told the postmaster. "He deserves that big one you've got hid on that shelf behind you."

Oleman turned, picked up the giant candy bar, and gave it to me.

"You know where the drinks are, Red. Get him one. What can I get you?"

"Baloney sandwich," father answered.

Oleman turned toward his left then turned right at the meat case. He took out the rolled balogna and thick-sliced it with a butcher knife.

"What's you want on it?"

"A slab of cheese and a tomato," father said.

"No pickles?"

"No pickles," father said, handing me a bottle of Dr. Pepper.

"She's here," someone called.

I turned around and discovered that the she in question was Sister Mary Magdalene.

“You’re gonna be late for the radio show, Sister,” father said.

“No, no...” Mary Magdalene smiled. “Be right on time. Don’t want to be sitting out front like I have to do when I go to the doctor’s office. I want to get there when it’s time to walk down the hall to the studio and the DJ turns on the On The Air sign. Need me a Pepsi...”

“Got a frosty one just like you want it,” Oleman said as he walked toward the General Electric refrigerator. He took a bottle from the top shelf with difficulty, for I could see it was stuck to the side of the ice-covered wall of the freezer compartment.

“How are you, young man?” she asked, mussing my hair with her left hand while he extended her right toward Oleman.

“Keep your money, Sister,” father said.

Oleman’s chin dropped.

“Oleman’s matching the silver dollar the boy gave Brother House for a love offering. Same dollar he got for finding the prize egg at church...”

“Lawdy be,” Sister Mary said, mussing my hair again. “I put up that dollar. I’ll give that old hoot Oelman’s dollar bill and get that silver dollar back for you, son.”

Before I could tell her not to, she began to speak quickly...

“Coloring Easter eggs is a fun Easter tradition. Nowadays, it’s become an art form. They sell many different kits for it. Coloring Easter eggs is only one of the traditions surrounding eggs on Easter. Parents tell their babies how the Easter Bunny hides the eggs, and them babies go on an Easter egg hunt...”

“I saw the Easter bunny this year for the first time in my life,” Oleman said. “Black and white flop-eared bunny it was. It weren’t no white rabbit like Alice followed and it weren’t no wild, brown rabbit like me and Cameron hunt...”

Sister Mary stared him down then continued...

“Every year I color eggs the same way. I'm good at coloring Easter eggs without a kit, with food coloring and natural dyes like my Mama taught us kids to do it. You color eggs, boy?”

“Yes’m,” I answered.

“Good for you... Do you know who started the tradition?”

“Your namesake,” father said.

“Well I’ll be John Brown, old boy, you do know don’t you. Mary Magdalene was a woman of some wealth and social status. Following Jesus Christ's death and resurrection, she used her position to gain an invitation to a banquet given by Emperor Tiberius Caesar. When she met him, she held a plain egg in her hand and exclaimed Christ is risen! Caesar laughed, and said that Christ rising from the dead was as likely as the egg in her hand turning red while she held it. Before he finished speaking, the egg in her hand turned a bright red, and she continued proclaiming the Gospel to the entire imperial house. Is that how you heard it?”

“Only thing I remember about it is that she was the one started it...”

“I gotta run, boys. You all listening to the program today?”

“Got a bunch of the men folk coming in atterwhile, Sister,” Oleman said. “We wouldn’t miss it for the world...”

“Bless your heart, old boy,” Sister Mary Magdalene said, smiled, and then rushed from the country store.

Men from Divine Ridge began to arrive a few minutes before nine o’clock. Most of them I knew by name. The couple I did not know I would ask my father about later.

Before Oleman finished ringing up their purchases, he turned on the radio, full blast.

“Good morning out there in radio land, dear hearts,” Brother House’s voice silenced the crowd that had gathered. “Sister Mary Magdalene and her quartet will sing for you now. What’s you got for us today, Sister?”

“We’re gonna try two songs: In the Garden and Bearing the Cross to Win the Crown. These are going out to Oleman and Red and all the boys down Divine Ridge community way. Key of C...”

A shout,” Amen,” went up from Oleman...

“You boys oughta be ashamed now,” Jason laughed. “Woman should kill you two...”

I didn’t know why he said that.

“Shut up and listen,” Oleman shouted.

“I’ll thank her next time I see her,” father said of Sister Mary Magdalene and her group. “They keep it up; they’ll be good before you know it.”

After the two songs, Brother House began to speak: “A- man! Good job sister... All you listeners take the messages from them fine songs to heart and send us your love offerings so we can keep this radio program going...”

“Any lover offerings this week?” Sister Mary Magdalene’s voice rang out...

“Nary a one,” Brother House said.

Oleman and father looked at me. I dropped my head.

“Blessed be all of you out there in radio land. Before our time is up, I want to say what God has laid on my heart. He has told me that I should speak to the young men out there in radio land. If you have a young man in your house, get him in front of the radio so he can hear this. It will be a blessing today...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted...

“The Lord God has told me that this world is full of temptations for everyone, but he has told me; bless his name, to speak to every young man out there listening this fine day... Let us pray...”

“Good, Lord,” Sister Mary Magdalene prayed. “We thank you for this beautiful morning you have allowed us to gather here in your presence. Go with us throughout the rest of this worship service and bless Brother House for being your instrument. We thank you for the young men gathered around the radio and we pray they get a blessing out of this message. We pray in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen...”

“A-man, Sister, hallelujah, a-man... You know, dear hearts, the Lord has laid it upon me to tell you young boys out there that the Devil tempts you with cigarettes. The Devil wants you to think smoking is fun. Well, it ain’t. Your body is a temple so the Good Book tells us...”

“Amen, Brother House... My body is a temple unto the Lord. I never smoked in my life. You young boys heed the message Brother House is giving you...” Sister Mary Magdalene interrupted.

“The Devil knows your heart, young man, whoever you are out there in radio land. He can read it like the Lord can. He reads it to work his own no good on you. I tell you young men in the radio audience, the Devil ain’t never up to no good. Give up them smokes and give yourself to God...”

“Amen and amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted in the background.

“And I tell you what the Lord told me just yesterday, young men out there in Divine Ridge and every other ridge and holler in this county, sons, don’t take to drink neither... Now I’m not talking about water or pop, them kind of drinks. I’m telling you the Lord don’t approve of beer, homebrew, and likker of all kinds. Young man gets imbibed, he defiles his body.”

“Red, he didn’t say anything about taking a little wine for the stomach’s sake, did he?”

“No, he didn’t, Oleman, bless his heart...”

A roar went up in the store that drowned out Sister Mary Magdalene’s amens...

“Now we’re getting close on time here, dear hearts out there in radio land. Before we go, I want to remind you to get those love offerings in the mail... Send your love offerings to me: Preacher House, Post Office Box 333, Divine...”

“He ain’t gonna do it,” Oleman cried out. “You sure you and Mrs. Mooringson’s grandson primed him about Jezebels?”

“I heard them,” I said.

“Maybe he will do it yet,” Father said.

“Before we sign off, brothers and sisters, and all you young men out there, let me tell you that the Devil is at work. He wants you to believe smoking and drinking is fun...”

“Amen!” Sister Mary Magdalene shouted.

“And I think we have just enough time...”

“He’s gonna do it,” father called out, looking toward me.

“The Devil works his way through Jezebels out there in the world, women who have been married three or four time and prey on our young men like mantis on flies. Young men, I’m telling you the Lord don’t approve of them painted hussies that lure you down the road of sin...”

There was silence on the radio...

After a moment, Brother House returned to his sermon...

“I said the Good Lord don’t want you young men out there within the sound of my voice to be sinning, lusting after no painted Jezebels..."

There was a longer silence...

Brother House cleared his throat...

More silence...

“I see that met with a cold reception,” Brother House cleared his voice again. “Get your love offerings in the mail, dear hearts, and we’ll be back on the air next Sunday, God willing...”

(Issue) 2

Avant(Poetry)

"Nargarjuna and Quohelet Break Windows Out of an Abandoned Garment Factory"

Michael Williams, Tennessee

“I didn’t think they could find anybody

who would work for less than us,

but they did.”

The old woman stares into her pot

remembers the sound of the sewing machines

each morning like an invasion of cicadas

to which she gave her days

and strength.

“Weren’t no piece work after that

so I went back to stripping tobacco

and cleaning rooms at the hotel

at the park.”

Later that night after consulting

with the philosopher, George Dickel,

Quohelet and Nargarjuna

adjourn to the site of

the abandoned factory.

Ouohelet picks up a rock

the size of a child’s fist

and hurls it at the few window

panes that remain unbroken.

“I’ll show you emptiness!”

Quohelet spoke

as the single smooth stone

flew toward the reflection

of the moon in Goliath’s eye.

“My granddaddy called them

winder lights,” Quohelet recalled,

“Now I see why.”

“If that ain’t emptiness,”

Nargarjuna agreed,

“Then I’ve never seen it.”

Michael Williams, Tennessee

“I didn’t think they could find anybody

who would work for less than us,

but they did.”

The old woman stares into her pot

remembers the sound of the sewing machines

each morning like an invasion of cicadas

to which she gave her days

and strength.

“Weren’t no piece work after that

so I went back to stripping tobacco

and cleaning rooms at the hotel

at the park.”

Later that night after consulting

with the philosopher, George Dickel,

Quohelet and Nargarjuna

adjourn to the site of

the abandoned factory.

Ouohelet picks up a rock

the size of a child’s fist

and hurls it at the few window

panes that remain unbroken.

“I’ll show you emptiness!”

Quohelet spoke

as the single smooth stone

flew toward the reflection

of the moon in Goliath’s eye.

“My granddaddy called them

winder lights,” Quohelet recalled,

“Now I see why.”

“If that ain’t emptiness,”

Nargarjuna agreed,

“Then I’ve never seen it.”

Avant(Art)

"Hurricane IV"

Donna Williams, Louisiana

Donna Williams, Louisiana

Avant(Story)

"Outside In"

Pamela Dae, Kentucky

Pamela Dae, Kentucky

Darlene wiped Amethyst Ablaze lipstick from her lips with a dirty napkin as Earl’s Camaro shuddered to a stop. Couldn't go back with Maybelline on her lips or the screws might figure she'd been gone.

Earl rubber-banded the gearshift to neutral, grabbed the crowbar from the back seat then scuttled around behind the car to pry open the passenger door for Darlene.

She slid low in the seat and emptied out the contents of the Wal-Mart bag: three tubes of Great Lash Mascara, two tins of Camel Spice snus, and one "Thrill" rechargeable personal massager. A tidy haul; she'd get enough buy her commissary for the next three months and then her minute'd be up. Darlene shimmied out of her jeans, pulled the "Go Vols" t-shirt over her head. Her prison-issue orange jumpsuit glowed malevolently in the backseat. She put her feet into the leg holes and slid the sleeves over her shoulders; the stiff cotton felt heavy as iron shackles.

When Earl wrenched open the passenger door, Darlene was ready.

"Earl, put this mascara under my bra in the back." She lowered the back of the jumpsuit, giving him full access while she carefully arranged each round tin of tobacco in the front cups of her bra. "Now all's left is the vibrator for Screamin Nina."

Earl snorted. "Don't reckon you'd wanna . . . "

"Earl. God. Don't be gross," she said, but snickered. "Anything coming?"

"All clear," he said.

The jumpsuit hanging from her shoulders, she tucked the vibrator neatly inside the back of the grayish-white granny panties. She stepped out of the car and stood hunched next to Earl as she snapped the front of the back together. "Sounds like bars closing, don't it, Earl?"

“Damn baby." Earl enveloped her body. "I hate leaving you here again. Five hours ain't enough. You call my cell phone once you make it inside now."

Darlene nodded once, sniffed back a few unshed tears. She knew Earl felt bad; he'd told her many times how sorry he was she got caught with his deal. But there it was, he was out and she was in and now it was almost over. She didn't want a blotchy, tear-stained face to be the last thing Earl saw of her for three months. She wanted him to remember those two hours at the Motel Six.

She stepped away and turned her back to him. “You don't see nothing?”

“Nah, baby. You’re good.” Earl leaned against the passenger door, grasped Darlene's ass in his hands and then turned her for a final kiss. He glanced up the hill. There was nothing there, just grass and trees and silence. If he didn't know better, he would have thought this was just another piece of one of the rich, loamy farms in the area; limestone swiss cheesing below the surface of the grass they called blue, glossy millionaire horses chawing on blades of it from above.

"I’ll make it back fine before the count as long as they ain’t looking for me. All quiet up there.”

The sound of gravel spraying caught them both by surprise but it was just an old Chevy parking across the road. A man in jeans and a windbreaker got out, glanced quickly at Earl's beater but kept his head down, walking toward the house with several brown bags of groceries in his arms.

“I couldn’t of stood this place another day if you hadn’t of got me this morning. I needed you in that motel room.” She pressed her groin against him, hard. “Don’t forget that. It’s you I need. This shit for the girls inside is just a little extra for commissary, you know? I hate having to ask you for money.”

Earl groaned. “Gal, don’t do that or I’ll take you right back to the motel and no Wal-Mart this time.”

Darlene giggled and ground against him tighter. With her head on his shoulder, she could see a mile back down the road. She heard a growling Harley, saw it approaching. “When it's over, Earl, let’s get one of them bikes and just go. God, I can’t wait til I get out of here.”

She closed her eyes, imagining freedom. A job in a Seven/Eleven or a grocery; coming home and fixing a dinner she wanted to eat, not something slopped out of industrial cans and barely heated; maybe somewhere down the line a pink baby with Earl's red hair wrapped in a soft, blue blanket.

"You better get now." Earl held her tighter for a heartbeat and then released her with the changing of the wind.

Darlene sighed, detached herself and edged up the hill. She heard the clang of the crowbar as Earl threw it into the floorboard and turned back to wave. But the man with the Chevy had come back out his front door and was looking at Earl too. He said something from across the black border of asphalt. It wasn't until he started walking towards Earl that Darlene recognized Corporal Brophy.

She scrambled several yards up the hill. There were no trees, no shrubs, not even any long grass between the road and the safety of the brick walls of the minimum-security prison. Only short-termers or low risks were housed here with the expectation they would stay put until officially released; you only had a short time to go and if you were dumb enough to screw that up, your Honor would make sure to give you enough time to see you didn't make that mistake again.

Darlene froze, her breath trapped inside her lungs but Brophy hadn't seen her. He stood in the middle of the road, focused completely on Earl, shouting at him to move the Camaro away from the prison grounds. And damn if that Harley wasn't headed right for his stupid ass. Jesus God, Brophy, look up.

He did not.

The bike barreled closer, the noise a freight train but still the damn fool didn't move. Surely to God Earl heard it. But Earl was standing as still as a catatonic holy roller.

Fuck.

“Brophy," Darlene shouted. She stood fifty yards away from the men, outside the low, wire fence that marked the grounds of the prison. "Brophy, move!”

He jumped at Darlene’s shout, saw the motorcycle headed for him and ran toward Earl. The bike swerved, continued on without slowing, the growl decreasing as it traveled down the road. Darlene watched until it shrank to a pinpoint on the vast blue horizon. When she turned back, Brophy's narrowed eyes fixed on her face.

“Thanks, Cooper," he said. "Course, that’s escape. I gotta charge you. You'll probably get transferred and do two more years.”

“Yeah.” Darlene put her hands behind her back and began walking up the road toward the gate.

Earl rubber-banded the gearshift to neutral, grabbed the crowbar from the back seat then scuttled around behind the car to pry open the passenger door for Darlene.

She slid low in the seat and emptied out the contents of the Wal-Mart bag: three tubes of Great Lash Mascara, two tins of Camel Spice snus, and one "Thrill" rechargeable personal massager. A tidy haul; she'd get enough buy her commissary for the next three months and then her minute'd be up. Darlene shimmied out of her jeans, pulled the "Go Vols" t-shirt over her head. Her prison-issue orange jumpsuit glowed malevolently in the backseat. She put her feet into the leg holes and slid the sleeves over her shoulders; the stiff cotton felt heavy as iron shackles.

When Earl wrenched open the passenger door, Darlene was ready.

"Earl, put this mascara under my bra in the back." She lowered the back of the jumpsuit, giving him full access while she carefully arranged each round tin of tobacco in the front cups of her bra. "Now all's left is the vibrator for Screamin Nina."

Earl snorted. "Don't reckon you'd wanna . . . "

"Earl. God. Don't be gross," she said, but snickered. "Anything coming?"

"All clear," he said.

The jumpsuit hanging from her shoulders, she tucked the vibrator neatly inside the back of the grayish-white granny panties. She stepped out of the car and stood hunched next to Earl as she snapped the front of the back together. "Sounds like bars closing, don't it, Earl?"

“Damn baby." Earl enveloped her body. "I hate leaving you here again. Five hours ain't enough. You call my cell phone once you make it inside now."

Darlene nodded once, sniffed back a few unshed tears. She knew Earl felt bad; he'd told her many times how sorry he was she got caught with his deal. But there it was, he was out and she was in and now it was almost over. She didn't want a blotchy, tear-stained face to be the last thing Earl saw of her for three months. She wanted him to remember those two hours at the Motel Six.

She stepped away and turned her back to him. “You don't see nothing?”

“Nah, baby. You’re good.” Earl leaned against the passenger door, grasped Darlene's ass in his hands and then turned her for a final kiss. He glanced up the hill. There was nothing there, just grass and trees and silence. If he didn't know better, he would have thought this was just another piece of one of the rich, loamy farms in the area; limestone swiss cheesing below the surface of the grass they called blue, glossy millionaire horses chawing on blades of it from above.

"I’ll make it back fine before the count as long as they ain’t looking for me. All quiet up there.”

The sound of gravel spraying caught them both by surprise but it was just an old Chevy parking across the road. A man in jeans and a windbreaker got out, glanced quickly at Earl's beater but kept his head down, walking toward the house with several brown bags of groceries in his arms.

“I couldn’t of stood this place another day if you hadn’t of got me this morning. I needed you in that motel room.” She pressed her groin against him, hard. “Don’t forget that. It’s you I need. This shit for the girls inside is just a little extra for commissary, you know? I hate having to ask you for money.”

Earl groaned. “Gal, don’t do that or I’ll take you right back to the motel and no Wal-Mart this time.”

Darlene giggled and ground against him tighter. With her head on his shoulder, she could see a mile back down the road. She heard a growling Harley, saw it approaching. “When it's over, Earl, let’s get one of them bikes and just go. God, I can’t wait til I get out of here.”

She closed her eyes, imagining freedom. A job in a Seven/Eleven or a grocery; coming home and fixing a dinner she wanted to eat, not something slopped out of industrial cans and barely heated; maybe somewhere down the line a pink baby with Earl's red hair wrapped in a soft, blue blanket.

"You better get now." Earl held her tighter for a heartbeat and then released her with the changing of the wind.

Darlene sighed, detached herself and edged up the hill. She heard the clang of the crowbar as Earl threw it into the floorboard and turned back to wave. But the man with the Chevy had come back out his front door and was looking at Earl too. He said something from across the black border of asphalt. It wasn't until he started walking towards Earl that Darlene recognized Corporal Brophy.

She scrambled several yards up the hill. There were no trees, no shrubs, not even any long grass between the road and the safety of the brick walls of the minimum-security prison. Only short-termers or low risks were housed here with the expectation they would stay put until officially released; you only had a short time to go and if you were dumb enough to screw that up, your Honor would make sure to give you enough time to see you didn't make that mistake again.

Darlene froze, her breath trapped inside her lungs but Brophy hadn't seen her. He stood in the middle of the road, focused completely on Earl, shouting at him to move the Camaro away from the prison grounds. And damn if that Harley wasn't headed right for his stupid ass. Jesus God, Brophy, look up.

He did not.

The bike barreled closer, the noise a freight train but still the damn fool didn't move. Surely to God Earl heard it. But Earl was standing as still as a catatonic holy roller.

Fuck.

“Brophy," Darlene shouted. She stood fifty yards away from the men, outside the low, wire fence that marked the grounds of the prison. "Brophy, move!”

He jumped at Darlene’s shout, saw the motorcycle headed for him and ran toward Earl. The bike swerved, continued on without slowing, the growl decreasing as it traveled down the road. Darlene watched until it shrank to a pinpoint on the vast blue horizon. When she turned back, Brophy's narrowed eyes fixed on her face.

“Thanks, Cooper," he said. "Course, that’s escape. I gotta charge you. You'll probably get transferred and do two more years.”

“Yeah.” Darlene put her hands behind her back and began walking up the road toward the gate.

Is(sue) 3

Avant(Poetry)

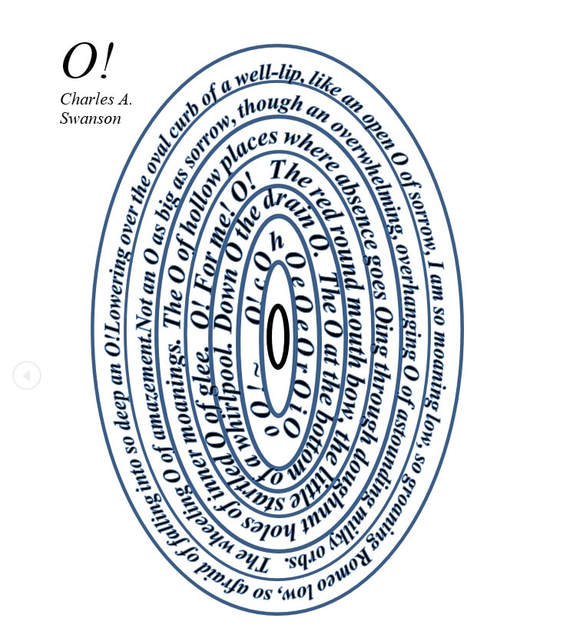

"O!"

Charles A. Swanson, Virginia

Charles A. Swanson, Virginia

Avant(Art)

"The Target"

Linda Regula, Ohio

Linda Regula, Ohio

Avant(Story)

"Sticky Red Stain"

Sabne Raznik, Kentucky

Sabne Raznik, Kentucky

Maddie dropped her sucker onto her textbook, picked it up, and popped it back into her mouth. She didn't like math anyway, so what did she care about the sticky red stain left on the page? Ahmed, the doctor’s son, sat in the seat behind her, pulling her hair. She sucked hard to keep from crying. Mom had said: "The bullies bother you to get a rise out of you. If you don't react, after a while they'll get bored and leave you alone." Ugh, she hated school.

"Change of plans, children." Mrs. Prater said. Something about her voice made Maddie forget her hair. "Today we're going to watch TV."

Those were the magic words: an explosion of cheers, slamming books, and chairs grating across the floor. One boy threw his basketball into the air and started up a UK chant (go Wildcats). Instead of sternly ordering silence, Mrs. Prater only grabbed a chair and stood on it to reach the TV.

Maddie felt something was wrong. She'd never seen Mrs. Prater's hands shake before and there were tears in her eyes. Maddie wondered if she should get under her desk and put her hands on her head like they did during drills. She glanced nervously out the class windows. It was still warm out. The rain that had tormented her while she waited on the bus that morning had since moved on, leaving a drowning humidity in its wake. It might as well still be summer, except that the leaves were beginning to wither a bit. A couple more weeks and Fall’s colour would take them, but not yet. The mountains were, as they had always been, inviting and safe like a favourite grandmother. She could see nothing changed outside.

The TV came to life, though its audio was buried under the cacophony of the children’s joy. Still, Mrs. Prater did not quiet them, but stood staring at it. She didn’t even get off the chair at first. Maddie couldn’t understand what she was seeing. She didn’t even notice when the children went silent on their own. In the end, all she would remember was shining glass, fire, black smoke, screaming, bodies falling perpetually like prematurely dead leaves, and the red stain on her textbook blurring with her tears.

****

Maddie couldn’t eat supper. Dad was very quiet and Mom looked from one to another perplexed. Finally, she said: “You going to let my fried chicken go to waste? What’s wrong with the two of you? You ain’t getting sick on me, are you?”

After a long pause, Dad said: “Jaime, we got to get us a TV in this house.”

“No now, Nathan, you know how I feel about a TV at home. They’re all good and well in their place, but you bring one home and next thing you know Maddie won’t play outside no more on account of she’ll miss her show, and then you and I won’t talk no more because it’ll be UK games morning, noon, and night. No, you can watch TV anywhere, but don’t bring it into my house.”

“I suppose it’s just as well today was your day off.” Dad said. “Nobody was eating out anyway unless to watch the TV.” He paused, scratched the line between his eyes that the coal dust had stained black no matter how much he washed. His eyes fell and lingered on Maddie. “They shouldn’t a let the kids watch.”

“Watch what?” Mom shifted in her seat, annoyed. “You’re ruining supper, Nathan. Eat up, both of you. I don’t work all day cooking on my one day off just to have you all turn your noses up at it.” Then to avoid any more talk about TV: “You know our mountain sits right under the air traffic path over these parts, and today there’s not been a single plane. Silent as Hades around here. Plumb uncomfortable strange. Haven’t you noticed?”

“Yep.” Dad answered.

“Well?” Mom said.

Maddie started crying. She couldn’t help it. “They died, mommy. Everybody died.”

“What?” Mom said, horrified. “Who died?”

“Let her go to bed, Jaime. I’m having a word with the principal tomorrow. She’s only 8. They shouldn’t a let her watch.”

Mom let out a long, resigned sigh. Well, she was going to have to let them talk about TV; no way around it now. “Watch what?” she repeated.

“Put Maddie to bed and I’ll wrap up this chicken for ol’ Sadie and her daughter in law. They’ll be needing it since her son drove a tour bus up there yesterday for a bunch from Central Kentucky. Reckon he won’t make it home now.”

“What are you saying, Nathan? You’re scaring me now. All of you are scaring me.”

“Put Maddie to bed and then I’ll tell you.”

****

Mom saw it on the TV the next day at work. She came home from the restaurant looking 10 years older. She went in her room, came out wearing the black cotton dress she kept for funerals, fixed up supper, and set it out like a robot.

“You talk to the principal?” She asked after everybody had sat down.

“Yep.”

“Well, what’d he say?”

“That it was history and the kids need to see history.”

“You tell him I’ll make him history if he makes my child watch something like that again. Has he lost his mind, Nathan?”

“The whole world has, Jaime.”

Mom ended up taking ol’ Sadie the chicken herself. Ol’ Sadie said she had no use for funeral meats yet. Her daughter in law took it when she wasn’t looking, whispered thank you, and tried not to cry. When they left, ol’ Sadie gave Maddie a red sucker. She couldn’t eat it. She just stuck it in her pocket and tried not to cry, too.

****

Maddie didn’t go to school for the rest of the week. She had belly aches and crying fits. She couldn’t sleep or had nightmares. She even quit going to her bed and slept with Mom instead. Dad never went to bed at all anyway. He sat up praying for ol’ Sadie’s son, praying he would eventually come home.

Mom took Maddie to work with her. When Maddie would go out among the tables, the customers would talk to her, give her quarters for the old jukebox in the corner, and always turned off the TV. But as soon as she went back to the kitchen, she would hear them turn it on again and go back to talking about politics. She didn’t understand any of it really, but she did not like the sound of the word “war”.

She went outside behind the dumpster in the parking lot and paged ahead in her history reader. There was a chapter on the American Revolution. It said it was the “War for Independence”. But it was all stories about “the flag was still there” and none of it helped her to understand what war is.

“I guess it’s a grown up thing.” She said out loud to the cat who stood guard against rats.

She put up the book and stretched out on the hot blacktop. The weather was getting cooler fast. She wouldn’t have been able to let her skin touch the blacktop like this a few days ago. She looked up into the sky, already that deep, rich blue usually reserved for October. Not a single line in the sky. Still there were no planes flying of any kind. Mom was right, the quiet of it was plumb uncomfortable strange. Staring at the blue sky. The hot blacktop burning her skin. She heard screaming.

“Is that my baby screaming bloody murder?” Mom cried, red from the kitchen heat and flustered from the sound.

“Found her in the parking lot.” One of the customers said. “She must have fallen asleep out there and had a nightmare.”

Mom’s boss put down a stack of napkins that she was filling a holder with. “You should take that poor baby home, Jaime, and maybe call the doctor. He might know how to help the poor little lamb.” She placed a dishwater hand on Maddie’s head and stroked it sympathetically. “My own babies are the same way and they’re teenagers. They shouldn’t a let the kids watch that.” She ruefully shook her head.

****

The doctor was nice and played games with Maddie. He let her play “Knock Down the Towers”. He said it’d be good for her. She drew pictures and sang songs and wrote poems. It didn’t feel like being at the doctor’s. She liked it.

At school, everything was the same like nothing had happened. Maddie couldn’t understand it because she knew it was just a show. Like the smile painted on a clown’s face. It wasn’t real. Because, of course, everything was different.

In math class, somebody passed her a note. She opened it slowly, wondering who would write her one. “I’m sorry I pulled your hair. It won’t happen again.” She pulled the red sucker out of her pocket and passed it back as a reply.

Now the bullies picked on Ahmed instead of her. So she went to where he sat alone at recess. “My mom says the bullies only want to get a rise out of you. If you ignore them, they’ll leave you alone eventually.” He didn’t say anything, just looked at her with sad, wise eyes.

That was the day that a plane’s engine ripped the quiet open and, after so long, it was loud indeed. Everybody came running out of the school to watch it. A lone army plane, flying lower than the commercial planes would when they resumed a week later - big and heavy with an unknown but dreaded cargo.

****

Five years later, ol’ Sadie finally gave up and held a funeral service for her son. There was no body, so there was no casket. Just a photo next to some flowers and a large computer monitor showing a slideshow of more pictures and videos. It was weird going to a funeral without a graveside service. Maddie wore her mom’s black cotton dress, since it fit her now. Her mom had to work that day and couldn’t make it, but she sent enough fried chicken to feed an army.

After the service, Maddie helped serve the mourners. Never is there as big a feast as at weddings and funerals! The whole thing was surreal, though. People talked about it like it wasn’t five years ago; they talked about it like it was yesterday. And the strangest thing, at least to Maddie, was the way everybody treated the doctor and his family. Oh, they still went to him for their ailments, but outside of that, he wasn’t welcome. Because of that, he and his family didn’t come to the funeral.

Maddie stayed behind to help with the cleanup. When she got all the leftovers together, Sadie’s daughter in law said to keep them.

“Everyone’s been so kind; we’ve got so much food at the house, there’s nowhere to put it all. Take that back home to your sweet mommy. She won’t have to cook when she gets home tonight.”

The crickets were singing by the time she and Dad headed home, but she asked Dad to drive the opposite way instead. The doctor lived in a big, fine home on the other side of the river. She rang the doorbell next to the oak door with stained glass and waited. A dog barked and she saw a dachshund galloping happily her way. Ahmed opened the door.

“I know your dad was good friend’s with ol’ Sadie’s boy once. So I brought this from the funeral. My sympathies for your loss.”

Ahmed took the load out of Maddie’s arms. “Anyway, I’ve got to get home and fix supper for Mom.” She said, feeling embarrassed.

“Wait,” Ahmed said and lumbered down the hall.

He was gone for some time. She felt awkward to say the least. She played with the dachshund to pass the time.

Finally, Ahmed came back to the door. “Sorry,” he said. “I had to put the food away first.” He reached out his hand. “Thank you, for everything.” In his hand was the red sucker.

"Change of plans, children." Mrs. Prater said. Something about her voice made Maddie forget her hair. "Today we're going to watch TV."

Those were the magic words: an explosion of cheers, slamming books, and chairs grating across the floor. One boy threw his basketball into the air and started up a UK chant (go Wildcats). Instead of sternly ordering silence, Mrs. Prater only grabbed a chair and stood on it to reach the TV.

Maddie felt something was wrong. She'd never seen Mrs. Prater's hands shake before and there were tears in her eyes. Maddie wondered if she should get under her desk and put her hands on her head like they did during drills. She glanced nervously out the class windows. It was still warm out. The rain that had tormented her while she waited on the bus that morning had since moved on, leaving a drowning humidity in its wake. It might as well still be summer, except that the leaves were beginning to wither a bit. A couple more weeks and Fall’s colour would take them, but not yet. The mountains were, as they had always been, inviting and safe like a favourite grandmother. She could see nothing changed outside.

The TV came to life, though its audio was buried under the cacophony of the children’s joy. Still, Mrs. Prater did not quiet them, but stood staring at it. She didn’t even get off the chair at first. Maddie couldn’t understand what she was seeing. She didn’t even notice when the children went silent on their own. In the end, all she would remember was shining glass, fire, black smoke, screaming, bodies falling perpetually like prematurely dead leaves, and the red stain on her textbook blurring with her tears.

****

Maddie couldn’t eat supper. Dad was very quiet and Mom looked from one to another perplexed. Finally, she said: “You going to let my fried chicken go to waste? What’s wrong with the two of you? You ain’t getting sick on me, are you?”

After a long pause, Dad said: “Jaime, we got to get us a TV in this house.”

“No now, Nathan, you know how I feel about a TV at home. They’re all good and well in their place, but you bring one home and next thing you know Maddie won’t play outside no more on account of she’ll miss her show, and then you and I won’t talk no more because it’ll be UK games morning, noon, and night. No, you can watch TV anywhere, but don’t bring it into my house.”

“I suppose it’s just as well today was your day off.” Dad said. “Nobody was eating out anyway unless to watch the TV.” He paused, scratched the line between his eyes that the coal dust had stained black no matter how much he washed. His eyes fell and lingered on Maddie. “They shouldn’t a let the kids watch.”

“Watch what?” Mom shifted in her seat, annoyed. “You’re ruining supper, Nathan. Eat up, both of you. I don’t work all day cooking on my one day off just to have you all turn your noses up at it.” Then to avoid any more talk about TV: “You know our mountain sits right under the air traffic path over these parts, and today there’s not been a single plane. Silent as Hades around here. Plumb uncomfortable strange. Haven’t you noticed?”

“Yep.” Dad answered.

“Well?” Mom said.

Maddie started crying. She couldn’t help it. “They died, mommy. Everybody died.”

“What?” Mom said, horrified. “Who died?”

“Let her go to bed, Jaime. I’m having a word with the principal tomorrow. She’s only 8. They shouldn’t a let her watch.”

Mom let out a long, resigned sigh. Well, she was going to have to let them talk about TV; no way around it now. “Watch what?” she repeated.